Forget Wimbledon, this is how the game used to be played, offering a cerebral as well as a physical challenge, as Gabriel Stone explains

Real tennis is a niche sport, often only familiar to the students at certain schools and those who have taken a wrong turn on the Hampton Court tourist trail. It’s a game that doesn’t just rely on physical brawn but also experience and mental strength, meaning its players get better as they age. Gabriel Stone explains this celebral, as well as physical, challenge.

Eventing has much in common with real tennis, played out against the backdrop of Britain’s most historic houses and consistently placing its older competitors at the top. Read more in Badminton: older horse riders at the top and take inspiration from the galloping grandfathers.

REAL TENNIS

Name a sport at which someone in their late forties can consistently beat a 20-year-old at the highest level; experience can outmanoeuvre youthful vigour; and battles are often waged against the backdrop of some of Britain’s most historic houses. Eventing springs to mind but for a steadily growing band of obsessives the answer is “real tennis”.

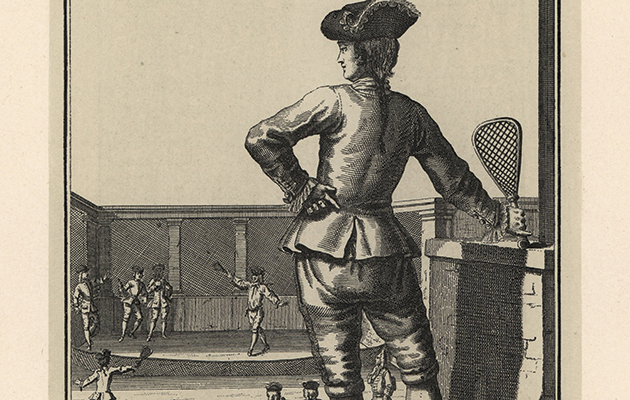

Many people will have stumbled across this quirky, intriguing game, perhaps while on the tourist trail at Hampton Court, as prospective parents around Canford School in Dorset or maybe even taking a wrong turn after a good picnic at Lord’s. What few realise as they peer into this cloistered world of tambours, grills and dedans, embellished with antiquated racquets and a fiendishly medieval rulebook, is that real tennis is no relic but a thriving sport.

REAL TENNIS: ROB FAHEY

By far the most prominent practitioner today is Rob Fahey, a chipper 48-year-old Tasmanian who, until this year, had successfully defended his World Champion title since taking it for the first time back in 1994. Speaking just ahead of the 2016 World Championships in Newport, Rhode Island – the game also has a home in the US, France and Australia – Fahey insists that his competitive spirit remains undimmed. But is spirit enough when your opponent, in this case American left-hander Camden Riviere, is almost 20 years younger and the format is a brutal best of 13 sets played, if necessary, over three days? The answer, it turns out, is not quite: 10 days later Riviere would go on to defeat Fahey by seven sets to two.

Despite this dramatic dethroning, Fahey would probably still stand by his observation that “being older is not as big a disadvantage as in other games”. Although no slouch on the fitness front, this is a man whose star quality and longevity ultimately derive from his unrivalled understanding of a sport that demands brains as much, if not more, than brawn. “Because it’s a walled game the court is a little bit of a funnel,” outlines Fahey. “With experience you know almost instantly where the ball’s going to go.”

Then there’s the tactical element, not to mention the confidence that comes from having experienced this level of pressure so many times. “With this game it’s more cat and mouse,” notes the man who lost the first two sets of his last World Championship final, also against Riviere, only to storm to victory by winning seven of the subsequent eight sets. “You can really structure a game in your favour and, to me, that’s the intellectual side of it more than all those chases and rules.”

REAL TENNIS: SENIOR SPORTSMEN AND YOUNGSTERS

This cerebral aspect of real tennis has an addictive draw, making it a thrilling discovery for many senior sportsmen forced to acknowledge their glory days on the squash court or rugby pitch are behind them. “There are so many elements to it, you’re always learning,” Fahey confirms, drawing a contrast with real tennis’s simplified descendant, lawn tennis. “Someone like Andy Murray has a limited set of skills that he has to get incredibly good at but once he’s done that there’s nowhere else really to go, and then the younger players will catch him,” explains Fahey. “With real tennis, there’s an infinite number of things to learn so you can just keep getting better and better.”

Of course, despite the long plateau offered by this sport and most emphatically demonstrated by Fahey, its top-level success ultimately relies on enticing youngsters into the game. That’s no easy task when the profile, court availability and funding of more mainstream sports is so much greater. One body founded specifically to tackle this challenge is The Dedanists’ Foundation, which has so far raised more than £80,000 to fund its programme of working with schools and clubs to bring a younger crowd into the game.

As its president, Fahey is closely involved with the charity’s mission and views this junior intake as vital to the future strength of the game’s elite level, which, in turn, has a trickle-down effect on the sport as a whole. While both squash and lawn tennis provide solid foundations for a switch to real tennis – Fahey himself was the former number one lawn tennis player in Tasmania – other sports offer equally valuable transferable skills. “Cricket or hockey players can be good at crossing over with that hard, low-bouncing ball,” he suggests.

REAL TENNIS: POL ROGER

As with any sport, sponsorship provides a lifeline for real tennis. It may never attract the multimillion-pound packages of other games but for certain companies this niche pastime draws in just the right target audience. Neptune is currently the game’s headline sponsor, but since the 1950s each year has seen fierce UK inter-club rivalry to claim The Field Trophy. In recent years, premier-division clubs have set their sights on winning The Pol Roger Trophy.

“We support eccentricity and enthusiasm,” explains James Simpson, managing director of Pol Roger UK and a keen player himself. The house’s connection with real tennis dates back around 20 years and is rooted in the notably large crossover that exists between this sport and members of the wine trade. Without the marketing clout of certain larger champagne brands, Pol Roger’s strategy has always been closely focused on recruiting fans at a formative stage in their wine-drinking journey. This sees the house sponsor an ever-expanding series of inter-university blind wine-tasting competitions as well as the annual Varsity real tennis match, a less widely publicised expression of Oxford and Cambridge’s rivalry.

Over time, this sponsorship has broadened its reach to the professional, international level that saw a Pol Roger bar refresh spectators of the Fahey-Riviere duel. “We’re both small players in a big world so we coexist nicely,” says Simpson of the Pol Roger/real tennis alliance. He echoes the need to recruit more players at a younger age, “otherwise, like golf, it’s just a lot of old farts”, and recalls a photograph that recently appeared of children from St Andrews braving a snow-clad court at Falkland Palace, the only club with the dubious distinction of having no roof. “We like to think they’re future Pol drinkers,” remarks Simpson proudly.

REAL TENNIS: THE CHALLENGE OF BUILDING COURTS

Running in tandem with this youth recruitment drive is the even bigger challenge of building more courts. Having fallen into decline after the Second World War, over the past 20 years real tennis has undergone a significant revival that has included the restoration of dilapidated venues such as The Hyde near Bridport, Newmarket and the second court at Cambridge. This has been accompanied by the construction of several new courts, including Bristol, The Oratory School in Reading, Radley College near Oxford, Middlesex University in Hendon and two at Prested Hall in Essex. As of summer 2016, Wellington College in Berkshire became the latest school to boast its own court.

That Wellington’s court has taken six years to reach fruition indicates the complexities involved in building a real tennis court from scratch. William Maltby, former chairman of the Tennis & Rackets Association (T&RA), Old Wellingtonian and a driving force behind this project, highlights just some of the obstacles. “The challenge initially was raising the money,” he reports. While Wellington College lent its support, the scheme still required a further £1.7 million to get it off the ground. More than 100 donors chipped in but, Maltby notes, “more than 90% was effectively funded by seven donors, including the T&RA”.

One of these benefactors, Peter Luck-Hille, also brought expertise in the construction of such an idiosyncratic facility, having previously endowed and closely managed the building of the Middlesex University court. His involvement at Wellington has been no less diligent, applying exacting standards to ensure the angle of the tambour was just right (52.7 degrees) and, records Maltby, supervising through the night until 8am on Good Friday morning when the concrete floor was poured.

REAL TENNIS: RUNNING A SUCCESSFUL CLUB

As if finding a suitable location and landlord with the requisite long-term view wasn’t enough, the distinctive height of any building that houses a real tennis court can cause the whole project to fall apart at the planning permission hurdle. At the end of all this, Maltby adds, “You need to be confident you can run a viable club.” As with its Radley and Canford school counterparts, the new Wellington court offers not just a resource for pupils but the wider community. Positioned within a sports complex that is open to the public, the club can tap into an existing base of 2,800 members, a good number of whom are likely to be sufficiently curious to pick up a racquet and venture onto the court.

Ready to welcome them – and anyone else who steps through the door – is Dan Jones, who joined Wellington last year as head professional of its real tennis court and immediately threw himself into the task of drawing up a comprehensive management plan to secure its future success. With particular experience in developing junior programmes, both at his previous club, Seacourt, and on a national basis with the Dedanists, Jones is ideally suited to inspiring Wellington pupils and young local residents to embrace his sport. “It’s open to all,” he emphasises. “If I can get someone on court, I’m fairly confident I can get them to fall in love with it within 15 minutes.” With any luck there’ll be plenty of people queuing up to put him to the test and, perhaps, even better, a future British World Champion.

REAL TENNIS: ACTIVE REAL TENNIS COURTS IN THE UK

*Readers of The Field are invited to try real tennis for themselves with a free lesson and tour of the new court at Wellington. Contact Dan Jones at dpj@wellingtonfitness.co.uk or call 01344 444244.

- Bristol

- Cambridge University

- Canford School, Dorset

- Falkland Palace, Fife

- Hardwick House, Berkshire

- Hatfield House, Hertfordshire

- Holyport, Berkshire

- The Hyde, Dorset

- Jesmond Dene, Newcastle upon Tyne

- Leamington, Warwickshire

- Lord’s, London

- Manchester

- Middlesex University, Hendon

- Moreton Morrell, Warwickshire

- Newmarket, Suffolk

- The Oratory School, Berkshire

- Oxford University

- Petworth House, West Sussex

- Prested Hall, Essex

- The Queen’s Club, London

- Radley College, Oxfordshire

- Hampton Court, Surrey

- Seacourt, Hampshire

- * Wellington College, Crowthorne, Berkshire (opening 2016)