Great halls, libraries, art and furniture have been used to venerate venery, creating the perfect environment for reflecting on the day, says Dr Hannah Clark

Carefully appointed hunters’ lodges, clubs and interiors have become an extension of foxhunting in the field. Dr Hannah Clark explains the four distinct phases of foxhunting interiors.

Appearances for the sporting gentleman are not confined to interiors, but extend to dress. Style was just as important as practicalities in creating the distinctive costume known today. Read Meltonian Dandy: by his clothes you shall know him.

FOXHUNTING INTERIORS

Foxhunting was not only performed in the field but ‘re-enacted’ over long winter evenings (often fortified by generous quantities of alcohol and storytelling) in the hunters’ lodges, clubs and interiors. A carefully chosen ‘sporting assemblage’ of sporting art, sportsmen’s libraries, taxidermy and hunting objects formed the stage on which the huntsmen chose to perform.

This ‘sporting assemblage’ was as much a tool in constructing identity as the physical act of hunting itself. From Henry Alken’s celebrated hunting prints in a sportsman’s library to Art Deco 1920s cocktail shakers, the imagery of the chase galloped across both practical and decorative objects. Yet, like all fashion, hunting interior trends were cyclical. Between the 1780s to the 1930s, the style, content and display of these spaces altered dramatically and went through four distinct phases, reflecting the changing status and geographies of the sport and those who hunted.

A ‘TOOZLING’ SQUIREARCHY

Before the advent of modern fox-hunting in the 1780s, 18th-century hunting interiors were largely considered unsophisticated relics of past aristocratic hunting glories. What remained was a world of ‘toozling’ in the hedgerows and squireish hunting, caricatured by Henry Fielding’s Squire Western from the novel Tom Jones. Fashionable hunting enjoyed by royalty and the nobility had been dealt a severe blow by the Civil War, where deer, deer parks and royal forests had been all but destroyed by Cromwell.

The Dinner, Humours of Fox Hunting, 1799, by Thomas Rowlandson.

Surviving aristocrats had also been lured away by new, fashionable entertainments in Britain’s growing urban centres. Thereafter, the countryside homes, hunting activities and interiors of any remaining rural gentry were considered old-fashioned.

One such hunter’s interior was described thus: “His house was perfectly old-fashioned… He made all welcome at his mansion where they found a house not so neatly kept as to shame them, or their dirty shoes; the great hall stewed with marrow-bones, full of hawks, perches, hounds, spaniels and terriers; the upper side of the hall hung with fox-skins of this and the last year’s killing. The windows served for places to lay his arrows, cross-bows and other accoutrements.”

Whilst these early hunting interiors displayed hunting through physical animal trophies and painted depictions of game, polite society considered sporting art one of the least elevated forms of art, suitable only to be hung in the plainest rooms. Meanwhile, due to its inedible nature and status as the lowest form of game in the hierarchy of noble venery, the fox was rarely depicted.

CLASSICAL REBIRTH

From the 1780s, a new, modern form of organised foxhunting driven by a young, urban-centric aristocracy brought hunting and the latest hunting interior straight back into fashion. These hunters rejected the ‘uncouth’ hunting spaces favoured by the 18th-century hunting squirearchy and instead embraced light, elegant, classical interiors filled with fine sporting art, porcelain and silver as befitted their new status as classical sporting ‘Corinthians’.

This break with tradition mirrored new ideas about masculinity, gentlemanly sportsmanship and the larger rejection of older brutal forms of hunting, play and recreational pastimes. Young men desired refined hunting interiors to gather in. Drafty great halls were replaced by comfortable spaces in the home designed for convivial gatherings, and smart Gentlemen’s Sporting Clubs were much attended. Henry Alken’s, The Toast, 1828, shows men in formal hunt dress celebrating a hunt dinner in a tastefully furnished room fitted with carpet, marble door surrounds, a mahogany table, large crystal chandeliers and three large, gilt-framed hunting paintings. In Sir Francis

Grant’s Melton Breakfast, 1834, Melton Mowbray’s Old Club hosts well-behaved gentlemen taking hunt breakfast within a smart, modern room complete with portraits of huntsmen and prized hunting horses, and a white-clothed breakfast table laid with fine porcelain and silverware.

High Leicestershire’s hunting elite enjoying breakfast.

Gone are the animal hides, fox masks or images of death one might expect. With the exception of the fox’s brush and pads as trophies, the physical body of the fox was replaced with fox motifs in interiors, representing a transformation of the physically violent into the physically elegant. Silver stirrup cups in the shape of fox masks by top London silversmiths such as Paul Storr were highly coveted, while at Exton Hall, Rutland, the Noel Family of the Cottesmore Hunt, ordered “a new Statuary marble chimney piece with fine Secelian [sic] Jasper Grounds and Bacchanalian Tablet richly carved with Foxes Masks in a frieze”.

Soon, fashionable foxhunting imagery positively galloped across the interior. For the first time the sport created its own distinct visual identity, which differentiated it from other forms of hunting. Top craftsmen produced exquisite hunting-themed objects such as engraved lead-crystal goblets, Derby porcelain, silver Grecian wine jugs and lighting outfitted with ormolu foxes and hunting horns.

Sporting art also underwent a change in status. Now truly fashionable, it was moved to the principal rooms of the house and used to celebrate new sporting celebrity, both seriously and with wry humour through fine paintings and more accessible prints. Since foxes were never caught with the aim of consumption, these elegant men of the chase were never portrayed as masculine providers of food or abundance. Instead, paintings by artists such as John Ferneley provided the perfect vehicle for celebrating individual hunters, where the focus was on the hunter and his mount, not the hunted.

VICTORIAN VISUAL CULTURE

With the arrival of the Victorians and Edwardians came huge changes. Once again, foxhunting was subsumed into a larger hunting visual culture. Empire and the popularity and opportunities of big-game hunting facilitated new ideas of masculinity and martial daring-do. Foxhunters were often also big-game hunters, and many adopted the visual symbolism of big-game hunting in their hunting homes. Fashionable Victorian hunting residences favoured dark, baronial interiors. Additionally, these often violent depictions of sporting prowess and their display were firmly rooted in the concepts of the new Gothic Revival, medieval chivalry and Arthurian legends. Such displays complemented a larger European trend for the spirit of Romanticism exemplified in the continued popularity of Sir Walter Scott and artists such as Sir Edwin Landseer. Gone was much of the ‘lightness’ of Regency hunting humour. Generally, depictions of foxhunting took on a more violent and sombre note. Even the popular Regency Alken prints reproduced by sellers such as Ackermann & Son were altered so that the horses and riders adhered to Victorian tastes for heightened drama, the horses given flaring nostrils, rolling white eyes and fiery Arab heads.

A George IV stirrup-cup by Paul Storr.

The Victorian’s also ushered in a golden age of taxidermy. Their taste for trophy hunting and the ‘manly’ conquest of the natural world resulted in a return to what Ken Ames called Death in the Dining Room and led to a bonanza of taxidermy, where the physical body of the fox or hunter’s horse became prized household trophy items or were even reimagined as furniture. This taste for hunting trophy furniture was enhanced by the 1851 Great Exhibition, featuring German ‘antler furniture’ and displays of antlers en masse in neo-medieval great halls.

Taxidermy acted as important ‘conversation’ pieces and mementoes of a favourite day’s hunting, and was increasingly used for practical as well as decorative purposes. The famous taxidermy firm Rowland Ward advertised itself as ‘Mounters of all Mementoes of the Chase’, producing fox pad letter clips, fox head inkstands, fox paw button hooks and even fox head toothpick holders. Not to be outdone, your favourite horse’s hoof could be turned into a silver candelabra, or all four hooves utilised to become the legs of your new fireside chair.

Surprisingly, the most famous form of hunting trophy – shield mounted taxidermy fox masks – was a relative latecomer to the interior. Excluding the fox’s brush and pads, fox taxidermy had been rare in the Regency period. From the 1870s, Ward was credited with first mounting fox masks, initially with wooden oval mounts but by the height of the Gothic Revival he adopted the familiar Gothic shield shape.

Interestingly, the stereotype of the snarling fox head with its lip drawn back represents an alteration purely for the tastes of the owner. Unlike dogs, foxes cannot snarl but they appear to have taken their stylistic lead from mounted big-cat heads; customers wanted evidence of overpowering a fierce wild animal, not a docile trophy. The red fox had long been thought of as possessing catlike qualities and its ambiguous status may explain why it was stylistically grouped with felines rather than canines.

COLLECTING THE ‘OLD WORLD’

By the 1920s, the wheel of hunting taste had again turned. Victorian heraldry was rejected in favour of a Regency Revival, combining modern comforts and innovation. Light, airy, elegant interiors were reinstated and Regency hunting artists such as Alken and Ferneley were held up as the Golden Age of sporting art and highly coveted. Sporting art collectors, connoisseurs and private collections housed in purpose-built sportsmen’s libraries became all the rage.

The Quorn in full cry near Tiptoe Hill by John Ferneley.

Foxhunting had become international. Fashionable resorts such as Pau, France, and Middleburg, Virginia, created a new breed of hunter hungry to furnish his or her home appropriately. While American hunters gleefully embraced foxhunting opportunities in the English Shires they also purchased large quantities of Alken and Ferneley paintings, sporting books, objects and furniture, becoming the biggest purchasers of British hunting objects. These objects with their ‘Old World’ charm were used to display their wealth, social status and gentility in the ‘Leicestershire of America’, Middleburg, as a way of both aligning themselves with gentlemanly sport and distancing themselves at a time of mass immigration to the US from those Americans of new or commercial wealth. In 1930, Fortune magazine observed that around Hunt Country Virginia, “almost every available property has been snapped up and painstakingly outfitted with the Alken prints which Northern taste believes indispensable”. Unlike their British counterparts, who had acquired sporting art and books organically over time, Americans collected British hunting art and books en masse for their sportsman’s libraries, homes and clubs, thus modelling their new residences on English country estates. Tellingly, The Sportsman magazine and Country Life in America ran regular articles titled Estates of American Sportsmen and Portrait of a Country Gentleman.

Demand for English sporting books and art was considerable. Whilst hunting in the UK, Harry Worcester Smith of Massachusetts, USA, made regular trips to his Liverpool-based antique dealer, Howell’s Bookshop, which boasted more than 800 customers in America and supplied him with rare hunting books and prints. “Needless to say,” he boasted, “I was not long in bargaining for all of these rarities, and whereas English collectors are the losers, the library at Lordvale is the gainer.” Americans also bought specially constructed libraries to house their English collections. ‘The Sportsman’s Own Library’, advertised in The Sportsman, was designed to house 4,000 volumes, folios and prints, and was offered ‘constructed and decorated for approximately $15,000’, including decorative friezes on the cabinets copied from 18th-century hunting prints. In contrast, Major Burnaby’s rather careworn library at Baggrave Hall, Leicestershire, was more organically grown and featured irreverently placed taxidermy fox masks on top of the broken-pedimented bookcases in place of the typical busts of Aristotle or Plato.

A Regency, ormolu-mounted hanging light by William Collins, 1814.

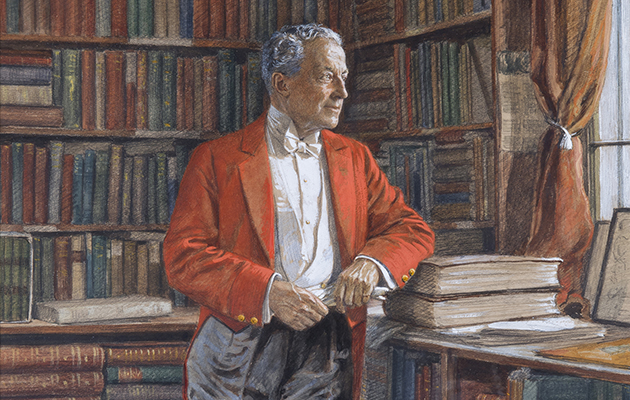

The importance of the sporting library can be seen in hunters’ choice to have their portraits painted not only on the hunting field but also in their libraries. Worcester Smith’s portrait shows him in evening hunting dress amongst his antique sporting books at Lordvale. By being painted there he positioned himself as a civilised sporting gentleman from a long-established elite family; attributes that his diaries suggest he cultivated.

By contrast, hunting interiors in America could be strikingly modern and innovative. At Ashland Farm, Virginia, hunting box of the wealthy New Yorker Amory S Carhart Jr, the use of old English sporting prints was decidedly modern. Photographically enlarged and used to cover the entire living room as a panorama, one of John Ferneley’s Leicestershire hunting scenes became the decorative setting for the antique furniture. Elsewhere, electric lamps and even cocktail shakers were decorated with antique hunting prints.

As the 20th century progressed, hunting interiors found their most confident expression in the United States. This was exemplified by the keen foxhunter Paul Mellon’s magnificent collections of British sporting art in Virginia, and the Virginian doyenne of English country house style, Nancy Lancaster, with her MFH husband, in Virginia and at Kelmarsh Hall, Northamptonshire. Latterly, Virginia’s coveted Hunt Country Style has become the subject of upmarket books and magazines. Most tellingly, Ralph Lauren has built his internationally successful lifestyle brand around the idea of the Sportsman’s Interior.