The traditional Norfolk jacket is intertwined with the warp and weft of rural life, and is enjoying a revival among those who want to look the part on the peg, says John Clements

Without doubt, I have an inner peacock and quite often things catch my eye and become part of my dressing-up box: the Liberty silk dressing gown from an Oxford second-hand shop or the velvet smoking hat and jacket that drew much mickey-taking from my children. And next on my list is the Norfolk jacket.

This shooting classic is different, harking back to an era of mutton-chop whiskers, hammerguns, duelling with bad guys on staircases and so on. It has a whiff of grandeur to it, too. But this was not what first attracted me to the Norfolk jacket. The single feature that caught my attention was in fact a space where the breast pocket would be. I shoot from my left shoulder, you see, and as fellow lefties will know, if you try to shoot in a ‘typical’ jacket, the toe of your stock may well catch in your pocket. Which is pretty frustrating at best and dangerous at worst.

Keeping the flag flying for the Norfolk jacket

Nature’s changing course has been handy with the clippers where these splendid garments are concerned, and whereas fleece gilets, skeet vests fashioned in tweed and spacious waterproof shooting coats (which, I must add, have reached their state of popularity because they make a great combination when on the peg) are available everywhere, only a few places have kept the flag flying for the Norfolk jacket.

Good news is at hand, though. Recent sales figures from London’s fieldsports emporium Farlows reveals that a revival is under way. To Pall Mall then, and a meeting with Farlows’ buyer Jack Gregorie to discuss the future for the jacket. “The overseas market has been the strongest for a while, mainly the USA and some in continental Europe. But there has been a huge rise in interest in the UK over the past two years,” says Gregorie.

Farlows’ new Norfolk jacket is the perfect sporting companion

To meet demand, a new Farlows Norfolk jacket (and matching breeks) have been designed. It’s a handsome garment, outwardly traditional but carrying the 18 months of design and development with the characteristic ease you might expect from Farlows, made from a dark olive houndstooth check tweed and crafted at Lovat Mill on the banks of the River Teviot (available at the end of September, £695).

Steeped in history

The history of the Norfolk jacket is based, unsurprisingly, in Norfolk. There’s some contention over whether it was first invented by Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk or Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester. Its origins may be otherwise but it is fairly certain it was the then Prince of Wales’ (later Edward VII) sporting of it in the 1860s that boosted its popularity. However, gunroom manager at James Purdey & Sons Nicholas Harlow says there is little evidence that he ever wore one. Indeed, the only image I can find of him wearing one was an advertisement for Colman’s starch.

Whatever the derivation of the jacket, it became a staple of outdoor life for 100 years or more. Intertwined with the warp and weft of country life, the Norfolk jacket was seen much further afield as well. Photographs of George Mallory on his fatal trip to conquer Everest in 1924 show him wearing one. But even Everest is not the greatest height one is believed to have scaled. In the 1930s, nearly 10 miles up in a purpose-built aluminium gondola, Auguste Piccard, was said to have worn one.

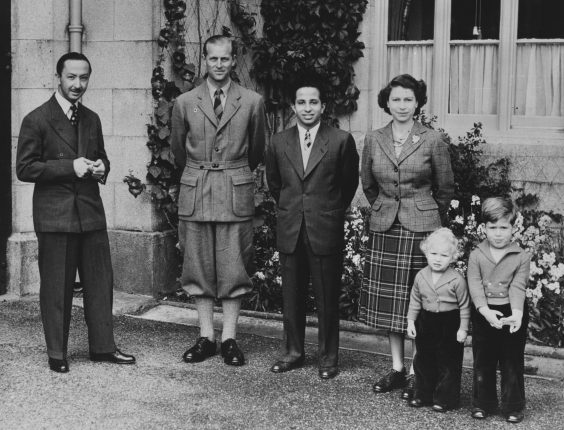

In more recent years, HRH The Duke of Edinburgh had one, as did angler Chris Yates. It even got a mention in the BBC comedy Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads in the 1970s. Tellingly, though, possibly because of its fade from popularity, it became a bit of a cliché (Jed Thomas, the ‘Arse!’ character from the 1990s TV series The Fast Show, often wore one).

An advert from 1890 depicting King Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, shooting in a Norfolk jacket.

A hard-wearing garment that will last for years

If its history is a little blurred, its renewed following is perhaps easier to understand. As Peter King at Bookster Tailoring says, the Norfolk jacket is an outdoor garment that when properly tailored to the measurements of the client will be hard-wearing and last for years. Not only that, but when time, bag straps and briar take their respective tolls, it can be repaired. We think of technical fabrics as modern things. Although breathability and elasticity are facilitated by modern processes, suitability for purpose was arrived at in the Norfolk jacket.

Movement is key. Whereas modern clothing might stretch or just hang around you in folds, the Norfolk secretes this additional space about you, proffering it when the need arises. Action backs in jackets are not unfamiliar to us, many a modern jacket and shooting coat has them, but the Norfolk has other tricks up its sleeves – or more accurately around the torso. There are two distinct types of Norfolk: the full and the half, the key difference being the belt. The belt on a full Norfolk goes all the way around and on a half Norfolk only appears on the back. In both cases, one of its jobs is to stop that icy blast that, given half a chance, would whisk up your back and remove your kidneys. Again, hardly revolutionary, but that is not the whole story.

Closer inspection reveals the jacket’s exoskeleton

To the casual onlooker, a Norfolk jacket looks like any other jacket. Closer inspection, however, reveals a sort of exoskeleton, a chassis almost. From the yoke at the front, which can conceal extra cushioning for the butt of your gun, falls a pair of straps, which conceal small but functional pockets. The straps carry on until they reach the belt. The belt sits across the top of your hips and supports and stabilises the weight of anything in your pockets, whether it is a hip flask or 25 or more cartridges. Once strapped to your hips, they have almost no effect on your shoulders, giving you free movement.

This is not all, because the Norfolk is roomy around the chest and if put together properly, there will be an almost blouson effect created by the belt and this roominess. So whether it is a covey of partridges bursting over a hedge or a gale-assisted cock bird heading over a lofty belt of trees, the only thing to slow you down is the sloe gin.

This Farlows’ Norfolk jacket – with collar turned up – is of a half-Norfolk style as the belt only appears at the back

A rebellion against the norm

So what has drawn me to this rebellion against the norm? A defiant cry against homogeneity? Middle age’s last hoorah before the stairlift catalogues start filling the post box? A feeble fist shaking at the modern age of mass production? As I have said, my initial attraction to the Norfolk was the lack of chest pockets. I am a left-hander and the placing of chest pockets on off-the-peg jackets is ruinous to smooth mounting and dismounting of a gun.

But my other reason for getting one is that they are fun. Almost as soon as I tried mine on, I realised that what I really needed to go with it was a pipe. I don’t smoke, but I carry a pipe when I’m shooting in my Norfolk because it is, well, fun. It is like a form of cosplay, borrowing the garb of the old boys in the photographs that grace the game diaries and walls of half-lit passageways, animating their frozen Edwardian contemplative state, walking in their footsteps. Like old guns, the Norfolk jacket worked then, and it still does now.

Interested in vintage kit? Read our guide to vintage shooting and hunting clothing. Or need help in knowing what to wear in the field? Click here.