Keeping a gamebook is one of the oldest sporting traditions, enjoyed by young and old alike, and as important now as it ever was says Ed Wills

Keeping a gamebook was obligatory when you started out shooting in my day,” says Sir Johnny Scott, who made his first entry at the age of nine. “Much of my early record-keeping was just rabbits but by the time I’d reached 16, it had really started to fill up.”

Whereas the left-hand page of Sir Johnny’s gamebook is set up to record the bare facts of shoot location, names of the Guns attending and the species shot, the right-hand page is more lyrical. “It is more of a diary form,” explains Sir Johnny. “I record the weather and how the birds actually performed. It is a pleasure to read back at the end of the season, partly out of respect for the quarry.” Given the level of detail, such enjoyment at reliving the days through his gamebook is unsurprising. It is immersive. He mentions each drive and everyone involved; not only the Guns but beaters, keepers, pickers-up and their canine companions.

Freddie Braithwaite-Exley also has a keen eye for detail, which is evident in his fishing diary and gamebook. Both were given to him when he was 10 by separate godparents after he caught his first salmon and shot his first pheasant. “They are exceptionally smart things with lovely leather covers. I have been using them for about 20 years now,” reveals Braithwaite-Exley.

Each journal has room for dates, locations, companions, species weights, weather conditions and comments. For Braithwaite-Exley, the overall joy of owning a gamebook comes from recording such details. “The gamebook is also stuffed full of game cards from shoots all round the country, which are fun to pore over occasionally,” he says.

“I like to look at my fishing book when I’m returning to a river; it’s great for looking back and seeing how days and weeks compare.” The River Findhorn features prominently, and Braithwaite-Exley has noted the heights of each pool that produced fish. He also records the flies and lines. “Reading back over 15 years, it is interesting to me to see I’ve caught a lot on floating lines and small flies but that more recently the majority have been on sink tips and brass tubes,” he says.

Such comparisons and how the experience can differ at a place one has visited time and again over the years is also something treasured by Will Garfit. He is the owner of seven gamebooks, each filled to the brim with fascinating entries. He separates his journals into two categories: personal game diaries and normal shoot reports.

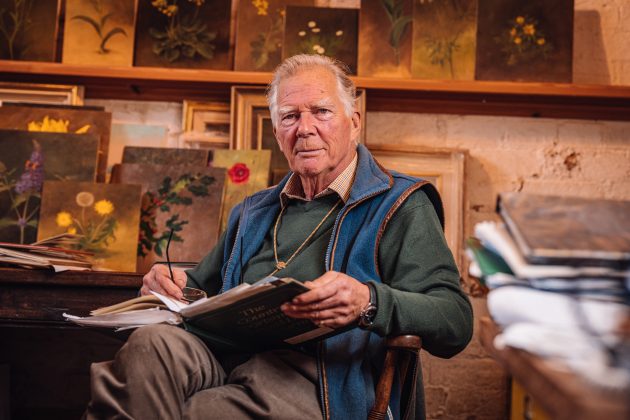

Garfit has kept an ongoing analysis of his shooting from his first days out in the field. “I was often pottering around a field for a squirrel or a pigeon when I started shooting,” he says. “I counted how many shots I took and how many cartridges I came back with, and then recorded it in my gamebook. I’ve carried on this way since 1961.” Through such analysis, Garfit has an excellent idea of how many cartridges to take out on a particular day. He has never been caught short since he started using his gamebook to make such calculations.

He also keeps a record of averages of his shooting accuracy on pigeon. Flicking through the pages, he finds an entry of a day where he shot 100 for 106 shots – a record in itself. “It is a wonderful way to recall the elements of a shoot day in the future,” he believes. “I don’t write a lot but I try to focus on the things that stand out, and inevitably there is always something to say.”

As Garfit is a skilled artist, he sometimes obliges to sketch something in a friend’s gamebook but not his own. “I’m much better at drawing things I’m looking at,” explains Garfit. “I do have a gamebook that is illustrated by other artists but haven’t yet found the need to input my own work into them.”

Many a great gamebook has a generational link to parents and grandparents. In Adrian Dangar’s case, his paternal great-grandfather purchased a gamebook on New Bond Street in 1892, the same year he bought a pair of Westley Richards shotguns. Dangar still shoots with one of these guns and used the gamebook. There is a photo on the front cover of his great-grandfather holding one of the guns.

“He only recorded formal shoot days in the gamebook,” explains Dangar. “He retired from the sport in 1913 so only filled the first fifth of the book. My grandfather never shot, so there is a gap until my father started to write in it in 1975. He completed 15 pages, detailing the years up to 1989 and this is where I took over.”

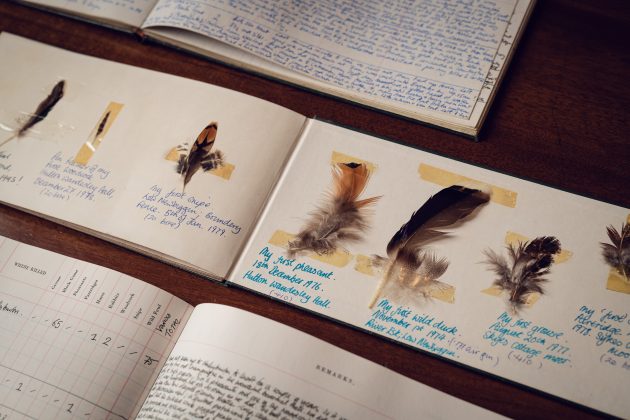

In 2021 Dangar finished the book; a prized possession as it holds priceless memories of three generations. Carrying on his great-grandfather’s work, Dangar occasionally sticks in the pin feather of a memorable woodcock and has kept feathers from all the first birds he has shot with the dates neatly written below each one. Dangar’s first entry into his own personal gamebook (not the grand family’s edition but a less elaborate journal) was a drake mallard in 1974. “I shot the drake on the River Esk in North Yorkshire with a .177 BSA air rifle, which I then sold to the builders working at home for 70 pence.” He still wishes he had received more for it.

Dangar is also the proud owner of fishing diaries belonging to Henry Meysey- Thompson, 1st Baron Knaresborough, his maternal great-grandfather. They tell of countless trips to the rivers Tay and Tweed, but more interestingly they describe what Lord Knaresborough did with his catch. “In those days, they used to sell all the fish they caught and gift fish they couldn’t sell,” Dangar says. “At the back of the book is a list of the people he gave a fish to; it includes the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. My great-grandfather also stuck some salmon flies into the book that were made in 1814 and are still in good condition,” he says.

Shoot records dating back to 1793 can be seen in estate gamebooks of Holkham Hall, home of the 8th Earl of Leicester, Thomas Coke. Holkham is known historically for its grey partridge shooting. However, thumbing through the pages, the records reveal an abundance of species. In 1877 1,215 hares were shot in one day, while a personal record of Maharaja Duleep Singh tells that he shot 780 partridges to his own gun in 1876.

Today, Lord Leicester maintains and updates the estate’s game- and stalking books when time allows. “The 7th Earl used to spend a lot of time after each shoot completing the gamebooks and would annotate anything of worth,” Leicester explains. “Regrettably I don’t have the luxury of time, though the books are diligently filled in for me by a long-serving member of my staff who has excellent handwriting and is a regular picker-up so understands the form.” Despite his busy schedule, Leicester keeps on top of his personal shooting records by keeping game cards neatly in a book of clear plastic pockets.

Neil and Serena Cross might have kept gamebooks since they were teenagers but differ in how they use them. “Mine is more like a diary,” says Serena. “I like to make the way I write about my days in the field more personal.” Neil keeps to the facts and figures with the odd anecdote added here and there. “There’s nothing like the feel of a gamebook in your hands,” he believes. “I think it’s terribly important that we keep a record of conditions and breeding stocks, not just bag numbers. After all, we’re very glad that our forebears did so.”

Serena’s current gamebook is one illustrated by Rodger McPhail and filled with elegant drawings of game species and photographs from each day. However, she likes to stick in game cards and, on one occasion, she kept a snippet of a newspaper covering the story of a fisherman who had caught a salmon in the flooded car park where the shoot she attended on another occasion met in the morning. The couple’s 20-month-old daughter Lamorna enjoys sitting on her mother’s knee gazing at the colourful illustrations inside the pages. Perhaps she will find one in her Christmas stocking in the future?

Rosie Whitaker and her husband Piers share one gamebook between them. “We tend to shoot together on the same shoot days, either sharing a gun or both of us in the line, so it makes sense,” Whitaker explains. “Keeping a gamebook is a wonderful way of capturing the day but it also serves as a useful reminder of who has invited us to shoot that season. This comes in handy when we send out our own shooting invitations the following year and ensures we don’t forget anyone,” she confesses.

Whitaker received her first gamebook from her father, Joe Nickerson, when she was 12 years old. It has huge sentimental value to her as he wrote a dedication in it: “To Rosemarie, from Daddy. Pull with a moving gun as soon as you mount to shoulder, keep swinging especially for crossers.”

As a teenager, Whitaker included personal notes on particular events that happened on shoot days: “In 1985, about my young spaniel I write ‘Judy behaved exceedingly well – she even sat through a drive not tied up’. And about her mother, ‘Janie whined a lot and was generally very disobedient, yet she did manage to pick up some difficult birds on the fourth drive,’” she reads.

One tip that Whitaker offers to anyone starting a gamebook is to record the events of the day as soon as you return from the shoot. “If you don’t write it the same day, a lot of the details disappear from your mind, and it is all too easy to mislay a game card.”

Those who keep, or have kept, gamebooks never regret doing so. It is never too late to start committing our best days to paper. If nothing else, it is an investment in the future; for reliving red-letter days in the comfort of an armchair by the fire.

If you are looking for a gamebook which includes space for pictures click here.