The family shoot day is the backbone of many a happy Christmas. Treasured memories and fieldcraft handed down the generations are the essence of life for the Christmas shoot says Hugh van Cutsem

As thoughts turn to Christmas and families getting together, there may be worries about a shrivelled turkey or even the odd crossword fuelled by excessive glass-emptying. However, the perfect tonic to such thoughts is the prospect of time spent in joyful outdoor surroundings, whatever the weather, with mad dogs, even more excitable children and a gun in hand as one searches out the spinneys and hedgerows to fill a gamebag for the Christmas shoot.

Those days, hopefully crisp and cold, provide the ideal antidote to frayed Christmas nerves as entire families get together after months, or perhaps even a couple of years, apart. For a start, it makes present shopping for nephews and nieces so much easier. All of my early shooting accoutrements, from cartridge bag and belts to shooting stockings and caps, when not hand-me-downs filled with the usual signs of wear and tear from an elder sibling, were unwrapped at Christmas. The joy of this is that the much-loved gun slip for my 28-bore I had as a lad is now proudly used by one of my children, and I hope will be used by a grandchild one day. A little longer lasting than anything Mr Fisher-Price came up with one suspects.

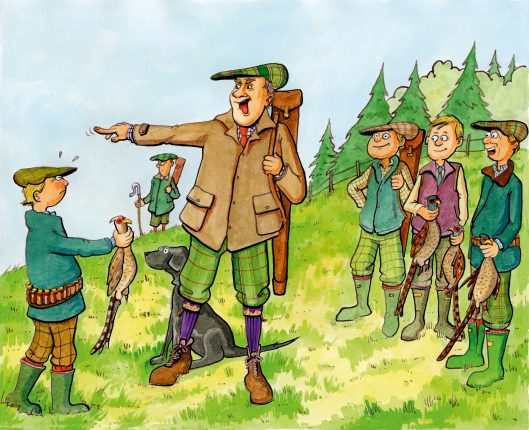

The family shoot day is the backbone of many a happy Christmas, and I know that for me growing up it was eagerly anticipated. First, there was the competitive element. Being one of four brothers all close in age, the question was always whose eye was going to get wiped. Would I actually fire a shot all day? Would one of my brothers accidentally shoot a hen pheasant thinking it was a cock bird (we all wished fervently one of the others would) and then we would all stand tutting behind my father as a grade-A bollocking would be delivered to the guilty boy and he would be sent off into the wastelands, confident he didn’t need a gun for the rest of the day.

As a youngster, sport over the festive period in Norfolk ran to pretty much every day other than Christmas Day, although we pushed hard to adopt continental European practices but to no avail. Out went the more formal types of driven days; this is where we went out with a stick in one hand, a gun in the other and a pack of dogs that ‘roamed’ freely (not that they really did anything different on our more formal days). Clothing also became a totally different format. Camo-patterned attire was in abundance and this is where four boys, my father and keepers really went to work.

These were days where, as young boys, we learnt fieldcraft that we then put to use later in life. You soon knew how to spot when dogs were just hunting or when they really had the scent of quarry in their nose. You learnt how to try to cut off the escape route that the old wily cock pheasant would take as you pushed out a thick pit, and where the best spots would be to catch up with these birds depending on time of day and weather. We would venture into the thick forestry blocks where we had shooting rights and plough through bracken and bramble to push forward a woodcock or two and pheasants that remained unbothered for the rest of the year. You also had to always keep an eye in the sky for a woodpigeon skimming over the treetops.

Rarely the cry of “fox” would go up and at once interest in all other game vanished, and we instantly had to engage brain and work out which line of escape the fox might take. If you called it right and were the brother who managed to cut it off, you immediately had bragging rights for days on end. We were a farm where wild game and ground-nesting birds took precedence, and I’m not ashamed to admit the fox was top of the control list: an admission that perhaps doesn’t stand me in great admiration with old-school hunting sorts. On one occasion one brother missed with both barrels his opportunity (he shall remain nameless) having done all the hard work to cut off Charlie; he turned back into the forestry block only for another brother to be far more accurate a couple of minutes later. Suffice to say, for one boy Christmas was essentially ruined.

These were days when the weather generally tended to be colder than the mild Christmas weeks we seem to get all too often now, and my mother did a valiant job of keeping us fuelled on tomato soup, sausage rolls and chocolate bars. I’m pretty sure we got all the nutrients you could ever need from that combination.

The organisation on such days was haphazard at best, and plans were always made on the hoof, but that was half the fun: no one knew what the day would bring. It also meant safety was paramount. As a woodcock flitted away down a woodland ride, could you shoot forward or not? It was excellent training to master one’s more hot-headed decisions. I know of one family shoot where one brother-in-law may have unintentionally forced another brother-in-law to take evasive action not once but twice during the same manoeuvre. At the end of the drive he went to complain to his father-in-law, expecting some reassuring words and a dressing down to be publicly dished out to the errant shooter. He was therefore somewhat taken aback when instead he was upbraided for being dressed head to toe in Realtree camo, and what did he expect if he was going to wear an outfit like that? It would be fair to say that this particular father-in-law took a rather more traditional approach to shooting-day clothing, even for the Boxing Day maraud.

Roll forward 35 years and how does Christmas week in Norfolk look now? Thankfully little has changed other than a small team of boys has become an entire squad of cousins with an even bigger mass of unruly dogs. Four boys have now been joined by four wives, 12 cousins and an unknown quantity of dogs, and with it the chaos has multiplied but so has the fun. Half the cousins are now shooting and the 28-bores of our youth are once again being put to good use, with the scars of handling being added to.

The other half of the cousins, being too young to shoot, approach their role of beating with a level of seriousness that can only be admired. They rightly feel that they are as important to the day ahead as any of the bigger ones with guns. Eyes light up as they are appointed ‘sergeants’ for the next manoeuvre and seem to take more than a little pleasure in commanding their other cousins into order. Hand them a walkie-talkie and they visibly grow three inches, and their radio chat would make anyone of a military background proud.

And for us four not-so-young-boys anymore it is a journey back in time, only our roles are morphing into what my father had to endure, and with it our appreciation for his infinite patience with us all has grown. Success is not measured in shots fired but in the smiles on small faces and the mutual enjoyment we all take in being together again in a setting that it would be hard to beat. They are days of simple pleasures and the making of memories that I hope all my children, nephews and nieces will take into their adult life, and I hope be lucky enough to continue.

Such days are all about being outside together as a family: the laughter, some tears as small people get hooked up in brambles or even, on one occasion, lost. One child (it might have been one of mine) somehow got separated from the rest of us in the woods. After frantic searching had failed to yield results and people were beginning to suspect the worst, a call came in to say he had been found. He had walked to a cottage on the edge of the forestry, politely introduced himself and informed the occupants that he was lost. When he was retrieved he was well restored on biscuits and hot chocolate. To this day we are unsure if he was genuinely lost or just fancied a break. When questioned he gives an enigmatic shrug.

My mother still provides the reviving food, exactly the same as we had and just as delicious decades later. She is also there to take the smallest cousins home, even when adamant through eyes half closing that they are absolutely fine and want to continue.

Memories made to last a lifetime have been carved out at Christmas: a cousin shoots her first woodcock; another beaming with delight as his learnt fieldcraft has ensured he put himself in the right position to catch out that cock bird. As life progresses, families separate as children grow up and follow their different paths, Christmas at ‘home’ is just the recipe to bring everyone back together; the marauds a perfect antidote to the intensity of being cooped up inside with each other. It is also a good opportunity to revel in each other’s successes, not to mention a deal of leg-pulling when things don’t quite go according to plan. Most importantly, it is heartening to see that in an ever-changing and evolving world some things remain unaltered and that the DNA of the much-cherished Christmas shoot continues to be what it has always wonderfully been.