This year marks the tercentenary of the birth of George Stubbs, a painter whose highly covetable equine portraits grace the walls of some of the grandest country houses to this day, writes Eleanor Doughty

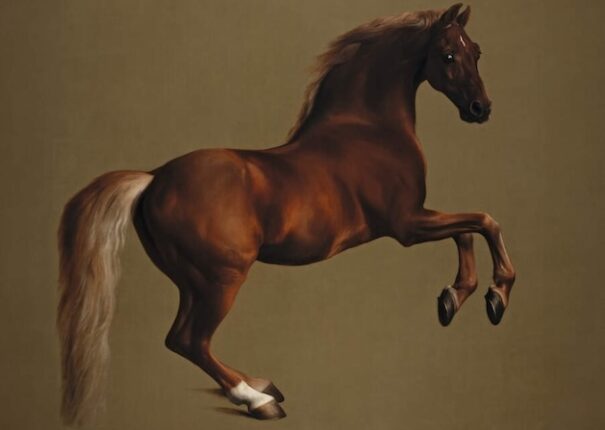

One of the best places in the bustling hubbub of London for a moment of quiet reflection is Room 34 of the National Gallery. Right in the middle of it hangs Whistlejacket, George Stubbs’ three-metre-tall portrait of Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham’s chestnut stallion.

George Stubbbs and Whistlejacket

Whistlejacket must be seen to be believed: it lends itself to the role of therapist – just as real-life horses are always able to do. In life, Whistlejacket, foaled at Belsay Castle in Northumberland, was temperamental and not particularly successful at stud. Immortalised in oil in 1762 and hung in his very own room at Wentworth Woodhouse, Rockingham and then the Fitzwilliam family’s South Yorkshire palace, he was a private icon for more than 200 years. When the painting’s transfer to the National Gallery was negotiated in 1997, Whistlejacket became a worldwide sensation – and George Stubbs with him. It is worth considering Whistlejacket now since this year marks the tercentenary of the birth of Stubbs.

George Stubbs has been described as one of the greatest horse painters in British art history

Anatomy of the horse

Relatively little is known about the master of equine portraiture – a status that Stubbs has retained in death but that in life he was desperate to shed. Born in Liverpool in 1724, he was briefly apprenticed to a Lancashire painter before moving to York to study anatomy. As Robin Blake, author of George Stubbs and the Wide Creation, describes: “He realised that no one had done a scientific examination of the anatomy of the horse, and he said, ‘Well, I’ll do it.’ It’s not clear what turned him in that direction but he just seemed to get horses.” In 1756 Stubbs began renting a farmhouse in the village of Horkstow in North Lincolnshire. He spent his evenings dissecting horses for what would become his 1766 work The Anatomy of the Horse, and his days with Sir Henry Nelthorpe, 5th Baronet, and his wife Elizabeth at nearby Baysgarth House. That year he painted the Nelthorpes’ son John out shooting with his two dogs. “It’s probably 60% sky,” says Tom Nelthorpe. “Very Lincolnshire. But I like how the dogs are painted and posed – it’s very naturalistic. If you squint, you can see how much detail he’s put into the grass.”

By 1759 Stubbs had begun to attract the attention of Lord Rockingham and his circle of fast-living landowners, who were happy to drop huge sums on portraits of their horses, their hunting and their dogs. Alongside Rockingham as early patrons of Stubbs were Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, for whom Stubbs painted the Charlton Hunt in 1759 to celebrate the revival of the Duke’s pack, and the exceedingly rich Richard Grosvenor, 1st Baron Grosvenor, for whom he produced The Grosvenor Hunt in 1762. These early successes assured Stubbs’ future career, and in 1763 he settled down in a house in Marylebone where he lived, rather abstemiously, for the rest of his life.

Even in his 79th year, he was remembered by the artist Ozias Humphry walking 16 miles to meet his client Thomas Villiers, 2nd Earl of Clarendon, at the Grove near Watford, tools in hand.

The Prince of

Wales’s Phaeton (1793), held by the Royal Collection

Where to see Stubbs’ works today

Today, Stubbs’ works are scattered around some of England’s loveliest houses. The National Trust has several in its care, including Hambletonian, Rubbing Down, the 1800 painting for Sir Henry Vane- Tempest, which hangs at the top of the entrance staircase at Mount Stewart in Co Down. Frances Bailey, the National Trust’s senior national curator, Northern Ireland, describes it as the “greatest star” of Mount Stewart.

Apart from the Stubbs paintings in the Royal Collection, which were acquired by George IV as Prince of Wales, the largest private collection of Stubbs in the UK is thought to be at Garrowby Hall in North Yorkshire. There are four at the Duke of Richmond’s Goodwood, and two within the Portland Collection at Welbeck Abbey, while Stubbs’ Tiger, which is based on a real tiger that lived at Blenheim Palace, remains there in the private apartments, having escaped sale by the family in the 1880s.

At Castle Howard in North Yorkshire, the 1773 painting of William Shutt, Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle’s groom, hangs in the crimson dining room, just to the right of where the house’s custodian Nick Howard sits when the room is in use. Once upon a time, the painting hung in Castle Howard’s private wing, in the sitting room of his mother, the passionate horsewoman Lady Cecilia Howard. “It’s just a lovely painting,” her son says, “though the expression on the groom’s face is rather haughty – he’s looking down his nose at the painter.” That the Castle Howard collection includes a Stubbs makes it all the more special, says Howard: “It’s not just a Stubbs on the wall, it’s of Frederick Carlisle’s groom, so the painting belongs to the house.”

The 3rd Duke of Richmond with the Charlton Hunt (1759)

Private collections

There are many Stubbs held in private collections, including a particularly lovely brace – one of a pair of leopard cubs and another of a pair of spaniels, which belonged to the commissioner of the latter work. The original commissioner, says the current owner, certainly “had the wherewithal to buy pictures”, and used Stubbs to enhance his collection. The Stubbs in this collection, as well as two further paintings that were a joint effort between Stubbs and another sporting artist, are particularly special to the current owner, who values them extremely highly within his wideranging collection. “The leopard cubs have been on the wall here throughout my life, so they’re almost part of the furniture,” he says. “But the two that are only partly painted by Stubbs are almost more interesting because they’re very unusual.”

Looking at any Stubbs today, it is hard to imagine how he could ever have fallen from favour. However, fashions change. “There isn’t really a cult of Stubbs,” says Robin Blake. “By the late 1790s he was regarded as old hat. When he died in 1806, the artistic community noted it but then his name faded. All the great horse portraits got darker and darker, and lost prominence.”

It wasn’t until the late 19th century that Stubbs’ flavour of British art began to regain strength, as new American superrich collectors entered the market. As Julian Gascoigne, director of early British paintings at Sotheby’s, explains, families such as the Vanderbilts and the Astors had a “very strong anglophile collecting taste. British 18th-century paintings were absolutely what they wanted – there was a desire to emulate the British aristocracy in the 18th and 19th centuries.” This fad was exemplified in 1921 when the railway magnate Henry E Huntingdon bought Sir Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy from Hugh ‘Bend’Or’ Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, for $728,000: the highest price ever paid for any work of art then.

Sir John Nelthorpe, 6th Baronet, out Shooting with his Dogs in Barton Field, Lincolnshire (1771)

With this, the decline of the country house and the contents sales that accompanied it through the early 20th century, Stubbs’ reputation was well served as his work began to hit the market. After the death in 1914 of Shire horse breeder Sir Walter Gilbey, 1st Baronet, 27 of his paintings by Stubbs were sold in one go. In September 1923 Eclipse sold for 105 guineas, and Huntsmen Setting Out in July 1929 for 4,200 guineas. By 1943, the year Vernon Henry St John, 6th Viscount Bolingbroke sold Gimcrack for 4,200 guineas, The Times was describing Stubbs as ‘one of the greatest horse painters in our art history’. When Gimcrack sold again in July 1951, it went for a record 12,000 guineas; at Christie’s again in 2011, it reached more than £22m.

Pumpkin with a Stable-Lad (1774) caught the eye of Paul Mellon, an important collector of Stubbs’ paintings

By far the most important Stubbs collector was the American philanthropist and keen hunting and racing man Paul Mellon, who bought his first painting, Pumpkin with a Stable-Lad, in 1936. Seeing the picture, he was ‘bowled over by the charming “Stubbs’ portraits have an immediate appeal for all kinds of groups” Were one to come across a lost Stubbs and take it into Sotheby’s, “that would be a pretty good day in the office”, says Gascoigne. “At his best Stubbs can command very strong prices. They’re not all worth £20m but a masterpiece by Stubbs is up there with the greatest paintings you could hope for from 18th-century Britain.”

Perhaps Stubbs would have been bemused by anyone celebrating his tercentenary. He ought not have been: no one ‘gets’ horses like Stubbs. “In the way that you can trace most portraiture back to the influence of van Dyck,” says Gascoigne, “most animal portraiture of the past century all goes back to Stubbs.”