Perhaps best known as the setting of the eponymous horse trials, this splendid Elizabethan country house is also home to a fine collection of heritage trees, says Graham Downing

Graham Downing is taken on a tour of the breathtaking Burghley parkland with head forester Peter Glassey to find out more about its ancient trees.

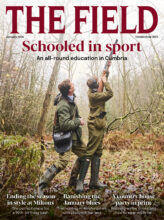

Available to hire, these fine sporting homes from home offer exceptional accommodation, top-notch hospitality and plenty of hot water, says Gabriel Stone.

BURGHLEY PARKLAND: THE STORY BEHIND ITS ANCIENT TREES

Universally admired as one of our country’s greatest treasures, Burghley, in its mellow stone splendour, could not be mistaken for any other house. Its cupolas and distinctive obelisk clock tower rise as an Elizabethan vision from the surrounding parkland and are familiar to countless visitors, not least the thousands who throng there each September for the Land Rover Burghley Horse Trials. But at least as spectacular as the house itself is its setting, the 1,300-acre park with its lake spanned by the imposing Lion Bridge, its rolling pastures, its sweeping vistas and, of course, its trees. Ranging from the majestic to the monstrous, from the ancient to the awesome, the trees of Burghley Park are arranged in clumps and avenues, in spinneys, copses and as splendid outlying survivors of a wood-pasture landscape dating back to the time of the Norman conquest. And while it ostensibly remains a vista of continuity, the parkland in fact is a living thing, constantly changing, evolving and renewing itself.

Many of the older plantings date back to the late 16th century, when the house was built by William Cecil, Principal Secretary and Lord High Treasurer to Queen Elizabeth I, who was to become 1st Baron Burghley and whose son Thomas was made 1st Earl of Exeter. After nearly 450 years, it should thus come as no surprise to find that Burghley hosts one of England’s most notable assemblages of ancient and historic trees. Nearly 100 years after Cecil’s plantings, however, the park had its first major makeover, for in 1683, George London, who was to become one of the greatest landscape architects of his age, together with his gardener Moses Cooke, laid out and planted a pattern of formal avenues and allées. Commissioned by the 5th Earl of Exeter, who had travelled widely in Europe with his Countess, Anne Cavendish, daughter of the Earl of Devonshire, the park was laid out in what was then the fashionable ‘gridiron’ continental manner.

Just 60 years later, however, all this was to change with the arrival of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, who over a period of 24 years remodelled the park in the new naturalistic style. Brown dug the serpentine lake below the house, using the spoil to create a new hill, which he crowned with oaks to frame a vista of Stamford’s spires. He swept away some of the earlier avenues or opened them up to allow guests tantalising glimpses of the house on their approach to Burghley, and though neither he nor the 9th Earl who commissioned him could ever have hoped to see the finished project, the landscape we see today is largely Brown’s work.

When head forester Peter Glassey arrived at Burghley in 1992, he was faced with three phases of landscape plantings, some of them thriving, some in decline and others nearing the end of their lives. “The remaining tall trees from the 1690 avenue plantings by London and Cooke were falling over. The felling and replanting of the mile-long Queen Anne’s Avenue was completed in 1997, and in 2003, we started work on the North Avenue, which extends 400m from the north front of Burghley House. We’ll fell the remaining 50 trees this winter,” says Glassey. “Avenue management needs to be brutal, because you want to end up with an even-aged feature.”

London and Cooke’s original avenues were planted with two double rows of Dutch clones of the common lime. The two clones were intimately mixed throughout the avenue, but for the replanting and restoration, the graceful ‘Burghley tall’ clone will be planted on the outside, and on the two inside lines, Tilia x europaea ‘Pallida’, a slightly messier and lower-growing lime, but one that flowers profusely to produce the most gorgeous fragrance, will be planted.

Felled trees are being replaced with saplings grown from the original plantings. “I’ve propagated stock from the existing trees by simple layering,” explains Glassey. “You bend over stems from a coppiced stool, peg them down so that they root, and after two years, you end up with new trees from the original.

“A major part of my work is to maintain elderly trees but also to provide age succession. We need not only to hang on safely for as long as possible to the trees we have, but we also need to plant new trees in a new suite of species that will provide continuity to the landscape and which will also be resilient to disease and climate change.”

This applies also to some of Brown’s signature plantings where trees have been affected by storm damage or disease, and it is considered essential to maintain the fabulous vistas that were meticulously planned by Britain’s best-loved landscape architect. Approach Burghley through the park’s south gate and you will see one of the most stunning. “Brown’s masterpiece was his southern approach,” says Glassey. “He planted an avenue of small-leaved limes coming down from the Great North Road, so that after your hard week in London, you would catch a first glimpse of Burghley House below you on your right, framed by Turkey oaks and English oaks. That view is lost as you enter the cutting.”

Capability’s Cutting, so well known to competitors on the horse trials’ cross-country course, was placed where it is for two reasons. First, to toy with the senses of the arriving guest as the house disappears and then reappears, and more practically, to lessen the gradient to enable a coachman to physically slow his team of horses so that they could stop in time for the Lion Bridge, which Brown had thrown over his new lake. “When you come to the bottom of the cutting and the bridge, the view opens up again, and that’s where you get the money shot of the west front,” says Glassey.

But even Brown could not have predicted bleeding canker, a disease that is slowly killing his horse chestnuts. Gorgeous as they might look in mid-May, with their candle-like spires of blooms in creamy-white splendour, Glassey no longer plants horse chestnuts to replace dying trees. Nor does he use ash. Ironically, one of the last major plantings at Burghley, a 60-acre wood to mark HM The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, contained some 30% ash, most of which is now suffering from ash dieback. “We noticed the disease about four years ago, where trees were getting twiggy and the crowns were thinning,” says Glassey. Where ash was sited next to a road, it was immediately felled for safety reasons and has since been replaced with a more resilient and diverse mix of species, including hornbeam, pedunculate oak, sessile oak, small-leaved lime, black walnut, wild service tree and Turkish hazel, which will offer future climate resilience. A similar mix of species is planned for the 70 acres of plantings in partnership with the Woodland Trust to celebrate Her Majesty’s Platinum Jubilee.

Another human threat to Burghley’s historic trees has been identified and addressed. Some years ago, it was noticed that trees close to the main horse trials site were declining and dying back. The cause was ‘event compaction’ resulting from the passage of hundreds of heavy vehicles over the root plates. “If you run vehicles over an existing mature tree’s roots you create impeded drainage, the mycorrhizal fungi on which the roots depend fail and the tree starts to go into decline,” explains Glassey. “It is said that a tree without mycorrhizal fungi is a tree waiting to die, so preservation of this rhizosphere is critical when managing any stock of trees, and especially veteran and ancient specimens. The estate is now actively managing its heritage tree collection by keeping events away from them with woven willow or park fencing, and by mulching with wood chip. The affected trees are recovering well.”

Other injuries are less easily preventable, such as the occasion when the bark was blown off a group of London and Cooke sweet chestnuts by a German pilot in 1941, whose stick of bombs mercifully landed on the park road and not on the house itself. Or the lightning strike a century or more ago on another venerable sweet chestnut, which blew off the bark and killed a major branch so that it looks today like the snarling head of a dragon.

But other veterans have quietly got on and done their own thing down the years. In the high park, to the east of Queen Anne’s Avenue and far from the public gaze, a sweet chestnut stands as it has for centuries. “I call it El Magnifico. With a diameter over 3.5m, the age data curve suggests it is around 600 years old, but Burghley hadn’t been built, so why is it here? It’s by far the biggest tree in the park, and according to the Tree Register of Britain and Ireland, it’s one of the countries’ 25 largest trees. The technical term for this tree is an Absolute Stonker.”

Today this venerable tree is thriving, dropping the occasional bough but readjusting and optimising its growth by throwing out new lower limbs. However, even stonkers like El Magnifico can suffer if not looked after. For decades the land around it was cultivated, and some of its neighbours still show the stag-headed signs of root damage where the plough came too close, but since 2013, this part of the park has been put down to grassland under a stewardship scheme and now the future of these ancient trees is assured.

Despite its massive girth and undoubted age, El Magnifico is a mere stripling when compared with one of the estate’s veteran oaks. From its hillside in the middle park, this ancient tree has watched medieval ploughmen plod behind their oxen. Perhaps it saw one Richard Cecil, William’s father, inspect his new estate at Burghley while Henry VIII sat upon the throne of England, and surely it witnessed Brown’s men dig the new Burghley lake a few yards away and erect a fanciful temple on the bank opposite. Now between 800 and 1,000 years old, and thanks to the continuity of the estate’s ownership by a single family, it has shaded countless generations of fallow deer and offered a home to more than 2,000 forms of life, from fungi to insects, birds and mammals: a nature reserve in its own right.

“It’s totally hollow, but it is a magnificent specimen and one of the healthiest trees in Burghley Park,” Glassey tells me as together we admire this ancient survivor. “It is voluntarily dropping the upper crown, which it no longer needs, and putting all its resources into counterbalancing itself against the lean that it has developed over centuries. It is managing itself perfectly well.” And it will go on doing so for maybe half another millennium. By then, the plantings of the early 21st century will themselves be nearing the end of their lives and it will again be time for the landscape of Burghley Park, if it is still with us, to face renewal.

Tours of Burghley Park and its ancient trees with head forester Peter Glassey can be arranged through burghley.co.uk/plan-your-visit/groups/gardens-talks-and-tours

Visit The Field magazine at the Land Rover Burghley Horse Trials this year (1-4 September 2022) on stand A15