Sleeve guns and gas-expelling fountain pens wouldn't look out of place on a James Bond set, but producing covert weapons became a serious business from 1940, says Mark Murray-Flutter

Gas-expelling fountain pens and sleeve guns are not exclusive to James Bond film sets. Producing special weapons became a serious business from 1940, as Mark Murray-Flutter explains.

For more on unconventional warfare, read The Imperial Camel Corps. Camels may have bad breath and bite, but they also make an excellent war mount.

SPECIAL WEAPONS

People are always fascinated by the unusual and the strange, and this is no different when it comes to special weapons. Since the invention of the gun in the 14th century, endless unusual or bizarre designs have been created and manufactured, generally meant to improve rate of fire and ease of use. Attempts were also made from early times to make covert or disguised firearms, often by concealing them as other objects, such as a walking stick or a key. Nevertheless, the use of covert weapons in warfare did not really figure as a serious consideration until the beginning of the Second World War.

The most common type of concealed weapon up to that point was the gas pen, a pepper-spray device looking like a fountain pen and openly sold by the great German hunting emporia, such as Eduard Kettner, in the 1930s for civilian self-defence. It was Winston Churchill who provided the biggest stimulus to the invention, design and use of a wide variety of “special” weaponry through the creation of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in July 1940, intended, in his words, to “set Europe ablaze”. Placed under the control of the Minister of Economic Warfare, SOE’s purpose was to damage the Axis war effort by helping to create and sustain resistance groups and to disrupt the enemies’ war effort, at first in occupied Europe and later in Asia. This would be achieved by supporting indigenous guerillas or through the use of trained and specially equipped agents.

Producing STEN guns at the Royal Ordnance Factory.

In addition to its supply and coordination role, SOE made a significant contribution to major military operations. These included: Operation Gunnerside, the attack on the German “heavy water” facility in Norway; Operation Harling, the destruction of the Gorgopotamos viaduct in Greece; and Operation Jaywalk, the sinking of 30,000 tons of Japanese shipping in Singapore harbour. These are but a few of the spectacular successes achieved by the men and women of SOE and resistance forces.

A large and highly efficient infrastructure supported SOE’s endeavours in enemy territory. Scientists and technicians designed and developed a wide range of specialist equipment. Innovative and sophisticated training programmes were set up by SOE training staff. Communications personnel established a global wireless capability and SOE liaison staff, working with the RAF and Royal Navy, ensured that agents and supplies reached their destinations.

SOE’s research effort into weapons and devices and their manufacture was managed under the cover name of the Inter Services Research Bureau (ISRB), which operated several workshops and laboratories throughout Britain. The Research and Development department, Station XII, was based in Aston House near Stevenage. Professor Dudley Newitt, a former soldier and chemical engineer at the Royal College of Science, London, was the director of research. In addition, there was a weapons section at Bride Hall, another country house in Hertfordshire, Station VI, which, among other assignments, was tasked with gathering weapons. One way of doing this was by public appeals in July 1942, September 1943 and early 1945, asking the civilian population to donate any weapon in their possession to the good cause. In this manner alone, more than 10,000 “untraceable” small arms were acquired for the use of resistance movements in Europe. Station VI sent more than 100,000 pistols and automatics of non-standard type, donated, captured or purchased, for use in the field.

The development of special weapons was the responsibility of the Engineering Section under the command of Lt Col Dolphin at Station IX, based at The Frythe, a lovely country house near Welwyn. To begin with, The Frythe had housed Section D (for “Destruction”), a minor, autonomous sabotage department under MI6. It functioned as headquarters to D section from the winter of 1939 until the establishment of SOE in July 1940, which took over both D Section and The Frythe. After 1942 and the entry into the war of America, SOE would share many of its inventions and designs with its new allies in the newly formed OSS (Office of Strategic Services), which also developed its own examples, in turn shared with the British.

Station XVb, the demonstration room, hidden within the natural History Museum in London.

Some of the properties in weapons most frequently requested by SOE and the OSS, for use under unconventional circumstances and behind enemy lines, were silence and easy concealment, to which scientists on both sides of the Atlantic turned their attention. These took the form of silent pistols, silent sub-machine guns, pen guns, crossbows and a number of even more exotic items.

One of the most famous special weapons or devices to come out of Station IX, used by both the British and the Americans, was the Welrod, a silent pistol probably named after Welwyn, the local town. The prototypes, in 7.65mm, were designed in 1942, manufactured at first by Station XII and from 1944, now in 9mm, by BSA. Indications are that 25,000 were ordered but not all were delivered. It is a single-shot pistol with an impressive ability to silence the shot. Not much is known of their use during the war, other than that they were sent to resistance groups in Denmark, Norway and France, and were supplied as equipment for Force 136, SOE’s unit in the Far East; by the end of the war, Force 136 had more than a thousand units at its disposal.

A variant of the Welrod pistol, also made by BSA, is the 7.65mm silent “sleeve gun”, described in the secret SOE catalogue as a gun “intended for use in contact with the target, but [which] may be used at ranges up to about three yards; the silencing element cannot be removed for replacement since the gun is not intended for prolonged use”. It is designed to be concealed inside the sleeve of a jacket and has a lanyard hole at one end to take a rubber band that can be attached just above the elbow of the user, who can produce the “gun” at a moment’s notice. Having used the device, the user just lets go and it will slide back inside the sleeve out of sight. All very James Bond, but how many were actually used is unknown. A few survive, a number in the Royal Armouries collection.

SILENT SUB-MACHINE GUNS

Also developed, on both sides of the Atlantic, were silent sub-machine guns. The British adapted the famous STEN MkII by adding an integral silencer, classifying it as the STEN MkIIS. For OSS use, the Americans adapted the .45in sub-machine gun, the M3A1, by adding a silencer and then classifying it as the M3A1 (Suppressed). Both these weapons were used by SOE, OSS and regular troops. They are recorded as being standard equipment for clandestine operations in Western Europe and were also used by the Allies in China and the Far East. Their use would continue after the war, especially in Indo-China.

Continuing the theme of silence, SOE had available for issue .22in bolt-action rifles fitted with silencers. The rifles were American in origin, Mossburg Model 42s and Remingtons, likely to be the Model 37, fitted with Parker-Hale silencers. They also issued a silenced version of the .22in Model B pistol made by Hi-Standard Mfg Co. Hi-Standard would subsequently supply the OSS with large numbers of silenced versions of its more modern Model HD .22in pistol. In 1944, ISRB explored the possibility of silencing the American M1 carbine, building a number of examples, only four of which now seem to survive, one being in the Royal Armouries collection.

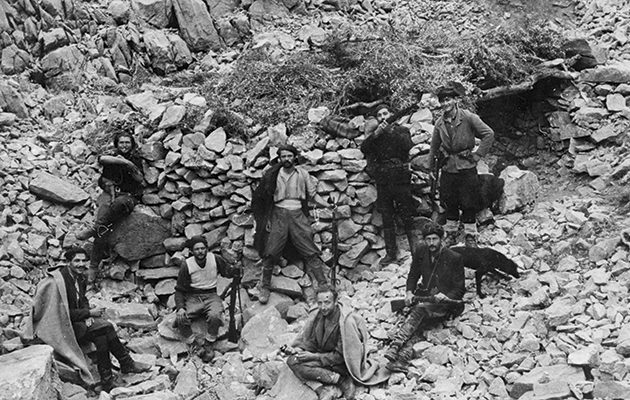

The SOE undertaking operations on Crete.

By way of exotic designs, there were a number developed by the boffins of Station XII and their American counterparts in the OSS. It is these that most fascinate students of “special operations”. In 1943, the Americans developed a small, pen-like device known as a “Stinger”, which fired a single .22in round; about 32,000 were made. The British had earlier developed a similar device resembling a fountain pen that expelled debilitating gas. SOE also asked London gunmaker John Wilkes to build a belt gun, designed to be worn by agents parachuting into Europe. It consisted of a .32in Colt automatic pistol mounted on a web belt and worn on the right hip. The firing device consisted of a Bowden cable that passed up the body, down the sleeve and terminated in a trigger mounted on the thumb or finger like a ring. About 12 were ordered and some were worn by agents parachuted into Denmark and Norway, as the Germans recorded seizing one, but few survive. There are also references to designs and samples for pipe, cigarette and cigar pistols that were acquired for test and evaluation, but these are unlikely to have been manufactured beyond the samples.

The last type of special operations weapon to be explored is the crossbow. It was thought by both the British and Americans to be a simple way of providing a silent weapon. The Americans developed two crossbows in particular, making both available to the British. The first was “Big Joe 5”, a shoulder-fired design using rubber bands for motive power, of which 13 were constructed and two are known to survive. It fired an 8oz aluminum dart or a special incendiary flare bolt. Also available was an unusual hand-held pistol crossbow known as “Little Joe”, which fired a dart with a metal broad-headed point. It was intended as a silent, flashless weapon for use by special operators to eliminate sentries or guard dogs. A few of the 27 made were sent by OSS to the Pacific Theatre of operations but no account has been uncovered of their use.

SOE and OSS were disbanded after the war, although the latter was to be reborn two years later as the CIA. The men and women of their research departments went back to their pre-war jobs, their contributions not to be acknowledged for some decades. The special weapons they designed and built no doubt found further uses in the years to come.

Mark Murray-Flutter is senior curator, hunting and sport, Royal Armouries Museum, Leeds