Tania Still refused to be separated from her love for hunting even off the field, a triumph reflected in her work, as Janet Menzies explains

RIGHT from the beginning, sporting art has been denigrated or, at best, dismissed as not worthy of consideration. When George Stubbs began work in the 18th century, equine and sporting subjects were considered fit only for inn signs because they weren’t religious or allegorical. His ground-breaking The Anatomy of The Horse did raise the sporting genre somewhat, only for it to be knocked back again in the late-19th and early-20th centuries by the arrival of modernism, which made it far too representational to be fashionable.

Of course, sporting art kept going, with Alfred Munnings berating the Royal Academy of Arts: “If you paint a tree, for God’s sake make it look like a tree! If you paint a sky, for God’s sake make it look like a sky!” In this century the furore has been further complicated by the increasing alienation on both sides of the country sports debate. This is the cultural maelstrom into which Tania Still has plunged by having the temerity to want to paint about her love of hunting. Still remembers: “At art college it was all very contemporary and I wanted to create contemporary sporting art. I wanted to paint about hunting. You are taught that you have to shock to be noticed, and hunting has always been very controversial.”

Still points out that hunting is a subject most find difficult: “I thought it was something shocking to explore, but my teacher said, ‘I am not going to teach you any more if you go on painting about hunting. I can’t extract myself from my feelings about it.’ His family had had a bad experience with a hunt going through their garden when he was a child.” Still’s experience of being attacked by shoot saboteurs was also traumatic, but apparently some shocks are more valid than others.

As usual we are left wondering why is it that Damien Hirst cutting cows in half for Mother and Child (Divided) should be acceptably, even applaudably shocking,while Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen is cultural imperialism?

Fortunately, Still is a brave artist. Before leaving Newcastle for London’s City & Guilds art school she made her own guerrilla installations: “I built stone cairns all over Newcastle. I brought stones down from the moors to build the cairns and moved them from place to place – the wheelbarrow was pretty heavy. Yes, I was a guerrilla sculptor but I did take them down, I don’t think anyone knew who did it.”

Still’s love of moorland comes from her upbringing in North Yorkshire: “We had a small grouse moor and I grew up shooting, I was always beating or flanking or counting or plucking… I got my first gun when I was 13, a beautiful 28-bore, and my uncle made me learn the gun safety poem.”

In the meantime, Still was pestering her parents for a pony: “What little girl doesn’t grow up loving ponies? I remember we had to wear yellow polo necks and balloon jodhs and it was all very itchy. I desperately wanted stretch jodhs. I was 16 when I got my pony and started hunting and fell in love with the countryside and the vistas and the atmosphere. Hunting was such a freedom for me.”

Like so many of us, Still responded to the empowering drama of crossing open country on horseback. She explains: “I had always wanted to be an artist. A cousin had trained in America and she used to give me little lessons – I was in awe of her.”

Still had found her subject but there were a few stiff obstacles in her way, not least a meltdown at exam time, which saw her failing art GCSE. “I persuaded my sixth form to let me retake and go on to do A levels and get an A. I had to go to university on a sculpting course, but managed to change to art. I remember in my first year seeing flyers offering a free day out in the countryside with beer and a picnic, and it turned out to be hunt saboteurs.”

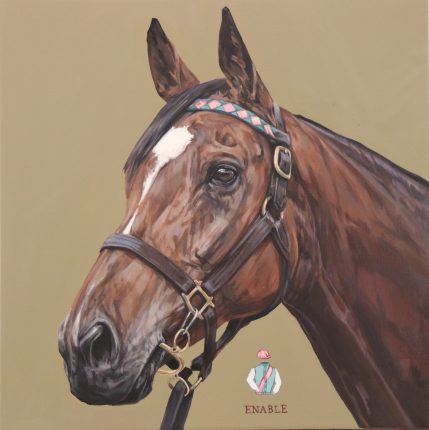

Still did not take up the offer. Her refusal to give in has paid off. She says: “I exhibit at Chatsworth every year and I was proud one year to find myself exhibited in the house alongside Frink and Hockney.” Her commissions are opening many stable doors, with recent subjects being two of the greatest racehorses of the century, Frankel and Enable. Surprisingly, she found the mare more daunting than the stallion: “Enable was intimidating. Her presence was amazing. She stood beautifully but she was very much the mare. Frankel though was welcoming – laid back, self-confident and relaxed.” Even so, it’s a long way from the little girl who just wanted a pony.

To contact Tania Still, call 07740411762 or visit: taniastill.com Look out for her work at The Compton, Cassey Compton, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire GL54 4DE and at the Rountree Tryon Gallery, Market Square, Petworth, West Sussex GU28 0AH.