Formed a century ago, the Imperial Camel Corps could use its mounts to operate at a distance from the main force, reconnoitring, raiding or protecting a flank. Allan Mallinson is an admirer

The Imperial Camel Corps was formed a century ago, and quickly grew into a brigade of 3,000 strong. Camels may be prone to have bad breath and bite, but Allan Mallinson finds himself admiring this unconvential war-mount.

For accounts of life upon a more conventional mount, read the original letters of the Cavalry in the First World War.

THE IMPERIAL CAMEL CORPS

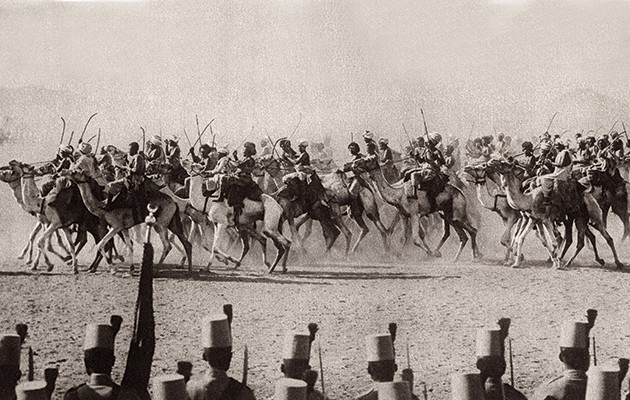

Australians of the Imperial Camel Corps near Rafah during the war against the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, 26 January 1918.

“Take my camel, dear,” said my aunt Dot, as she climbed down from this animal on her return from High Mass.” The famous opening line of Rose Macaulay’s whimsical 1956 novel The Towers of Trebizond, and that which follows perfectly sum up the English ambivalence towards the legendary “ship of the desert”: “I did not care for the camel, nor the camel for me.”

For the camel is the proverbial horse designed by committee. Refractory, with notoriously bad breath, and prone to bite, it is, as one Australian camelier of the First World War put it, “a pain in the a*se”. He meant it literally, as that famous camel-rider, Colonel TE Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia” played by Peter O’Toole in the film of that name), knew only too well: the reason he wore Arab dress, he explained, was that it was more comfortable than military uniform when astride the beast.

Camels were first domesticated in Arabia 4,000 years ago, providing meat, wool, milk and fuel (their dung can be burnt). Because they are so well adapted to desert conditions, their feet splaying for traction in sand, their stomachs able to retain prodigious quantities of water, they can cover great distances where nothing else could even survive, while also capable of considerable bursts of speed. A modern racing camel can canter as fast as a horse for an hour and more, and sprint at 40mph.

World War One Anzac Australian Camel Corps soldier giving his camel a drink of water from a chattu vase, 1916

The first recorded use of camels in war was in 547BC at the battle of Thymbra, in present-day Anatolia, when the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great defeated the Lydians, but although the British Army used camels for transport on the North-West frontier of India in Queen Victoria’s wars (in the Afghan campaign of 1879-80 70,000 transport animals were lost, most of them camels), the first serious use of “camel cavalry” was in 1884, when a corps was formed in Egypt for the ill-fated relief expedition to rescue General Charles Gordon, besieged in Khartoum. Military camels appeared in Egypt again in 1915, when the Maharaja of Bikaner offered his camel corps for the defence of the Suez Canal against the Ottoman Turks. They saw action in February that year when Ottoman troops mounted a raid on the canal across the Sinai Desert. It was not until January 1916, however, in response to an uprising of Senussi tribesmen in what is now eastern Libya, that the British Army in the Canal zone, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, raised its own corps of camel troops. With British, Australian, New Zealand and Indian contingents, many of them just returned from the failed Gallipoli campaign, it was named The Imperial Camel Corps (ICC).

THE FORMATION OF THE IMPERIAL CAMEL CORPS

A trainload of camels in Egypt belonging to the Imperial Camel Corps leaving Cairo for the Front in 1916.

The Bikaners were big dromedaries – one-humped camels – and some were taken into service by the Imperial Camel Corps as draught animals, but the lighter Egyptian camel was preferred for riding, with the female considered marginally more tractable than the male. Carrying a soldier, his equipment and supplies, they could cover an average of three miles in the hour all day.

The Imperial Camel Corps was a cosmopolitan outfit that gradually grew into a brigade nearly 3,000 strong. Unlike the cavalry, however, the unit command was called “battalion”, and the sub-units “company” , the men dismounting to fight instead of charging with sword or lance. As mounted infantry they were, in fact, reverting to the practice of the 17th century, when the dragoon moved about the battlefield on his horse but took to his feet to fight with a musket – in French, dragon – and was not allowed to wear spurs to avoid becoming entangled in the undergrowth.

Each camel company in the Imperial Camel Corps had six officers and 169 other ranks, four companies to a battalion. The 1st and 3rd Battalions of the brigade were recruited from the Australian Light Horse – mounted infantry whose members could use the sabre. The 4th Battalion comprised two companies drawn from the Australian Light Horse and two from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, while the 2nd Battalion was recruited from British Yeomanry regiments. There were two additional British companies for scouting, a machine-gun company formed from the Scottish Horse, the Lanarkshire Yeomanry and the Ayrshire Yeomanry, and a mountain battery of the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Garrison Artillery composed of 240 Sikhs with six nine-pounder guns that could be stripped down for portage. Together with a Royal Engineers field troop and signal section, Royal Army Medical Corps field ambulance, a detachment of the Army Service Corps and an ammunition column, the brigade was almost equal in strength to two conventional mounted brigades.

Mounted drill began with “barracking” – getting the camels to their knees. The rider tugged the halter rope downwards, making a guttural “duh, duh, duh”. Old soldiers were intrigued to find that the camel seemed to do everything by numbers: One! Bend the lower portions of the forelegs. Two! Sink down on the lower sections of the hind legs. Three! Fold the upper portion of the front legs on top of the lower. Four! Bring down the upper parts of the hind legs above the lower. Five! Shuffle and tuck in the feet comfortably. Six! Groan.

On the order “Get ready to mount”, the rider pulled round the head of the camel until it looked to the rear, placed his left foot on the bend of its neck and grasped with his right hand the peg at the back of the saddle. On the word “Mount”, he raised himself sharply into the saddle, throwing his right leg over the front peg (pommel), let out the halter full length, and the camel would instinctively rise – to the accompaniment of ferocious roaring that stopped as soon as the camels were up. On a dark night in a wadi the effect could be weird.

THE ADVANTAGES OF USING CAMELS

The camel may have been distinctly more uncomfortable to ride than a horse, but the sick and wounded were evacuated more expeditiously than in a conventionally mounted brigade. Instead of wheeled ambulances they were carried in “cacolets” consisting of two canvas stretchers balanced horizontally either side of a specially constructed saddle. In these a man could sit or lie full length, shaded from the sun by a canvas hood. Although the jolting motion could be trying for the badly wounded, they could be got back to the dressing station, for the camel could go where wheels could not. When the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) began its counter offensive across the sands of the Sinai Peninsula during the latter half of 1916, for much of the time neither horse artillery nor wheeled transport could follow.

The Imperial Camel Corps also had another great advantage, each man was issued with five days’ supply of food and water for himself and five days’ grain for his camel, plus 200 rounds of ammunition. Detachments from the Imperial Camel Corps could therefore operate at a distance from the main force, reconnoitring, raiding or protecting a flank during the advance, able to sustain themselves without a base.

To maintain the 40,000 camels in the EEF as a whole (both the riding animals of the Imperial Camel Corps and the draught animals for the EEF’s transport units), there was a camel remount depot and a camel hospital, with specially trained men of the Army Veterinary Corps. So effective were these that 70% of all camels sent to the hospital were returned to the remount depot as fit for further service.

The Imperial Camel Corps was raised and commanded throughout by Brigadier-General Clement Smith of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, who had won the VC in Somaliland in 1904 and for several years afterwards served in the Egyptian Army. His mixture of formal discipline and practical field soldiering proved a winning combination with independent-minded troops who had seen a good deal of fighting, and confusion, at Gallipoli. The pages of the corps magazine, Barrak (called after the Biblical warrior who banded with the prophetess Deborah to win victory over the Canaanites), are testimony to the high morale.

OPERATIONS BY THE IMPERIAL CAMEL CORPS

The Imperial Camel Corps had the distinction of operating in more areas than any other body of troops in the Middle East campaign, including alongside Lawrence’s Arab guerrillas harassing the Hejaz railway. During the EEF’s rapid push north to take Jerusalem in November and December 1917, under Lieutenant-General Sir Edmund (later Field Marshal Viscount) Allenby, they had a particularly arduous time, in action with the leading troops for five weeks without respite, advancing a hundred miles against stiff opposition. For days at a time the camels could not be unsaddled, so that by the new year they were manged and badly needing rest. When Jerusalem fell, the force was withdrawn to Rafah in Gaza, a sandy area in the south where the veterinary service could get to work, though some of the companies were instead re-horsed to serve with the mounted brigades. Northern Palestine, as well as having firmer terrain, had more plentiful water, and the camel’s one drawback – the length of time it took to drink – became more pronounced as the rate of advance increased.

Nevertheless, after nine weeks at Rafah the remaining men and camels were ready for action again, and in March the Imperial Camel Corps moved north to take part in the most strenuous operation yet – the advance over the Jordan River, the ascent of the muddy goat-tracks of the Mountains of Moab east of the Dead Sea, where no wheeled transport could follow, and on to Amman.

When the war with Ottoman Turkey ended, on 30 October 1918, the Imperial Camel Corps was rapidly broken up, with many of the camels given at Lawrence’s request to the Arab forces who had fought alongside Allenby’s men. Trooper Frank Reid of 12 (Australian) Company, 3rd Battalion, Imperial Camel Corps, perhaps typified the respect and even affection which the cameliers had come to have for their animals: “We were sorry for the camels. Although we often cursed them, when they were to be taken away from us we found that we had become quite attached to our ugly, ungainly mounts. The Arabs would not treat them as kindly as we had done, and we reckoned they were entitled to a long spell in country that suited them better than the rough and slippery mountain tracks of Palestine.”

REMEMBERING THE IMPERIAL CAMEL CORPS

The Imperial Camel Corps was not forgotten. In July 1921 a memorial statue was unveiled in Victoria Gardens on the Thames Embankment by the first commander of the Desert Mounted Corps, Lieutenant-General Sir Philip Chetwode, later John Betjeman’s reluctant father-in-law. The New Zealand and Australian prime ministers were present, along with Brigadier-General Smith and many of his former cameliers.

With the names of those who died while serving, the memorial is dedicated “To the Glorious and Immortal Memory of the Officers, NCOs and Men of the Imperial Camel Corps – British, Australian, New Zealand, Indian – who fell in action or died of wounds and disease in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine, 1916, 1917, 1918”.