Remembering Lawrence Burn, the last veteran of the regiment that spearheaded the Normandy landings on D-Day, 6 June 1944. By Allan Mallinson

In the grey dawn of D-Day, 6 June 1944, 20-year-old Trooper Lawrence Burn’s 35-tonne DD (duplex-drive) Sherman tank, its flotation screen raised, edged down the ramp of the landing craft into the English Channel. The storm that had forced the postponement of the Normandy landings for 24 hours had passed but 5,000 yards from the shore there was still quite a swell.

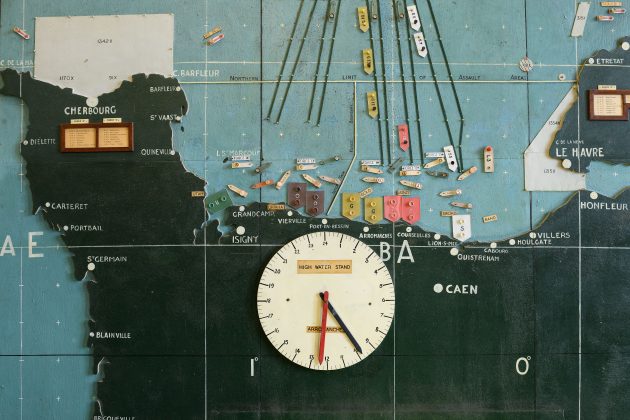

With the tank settled low in the water, just three feet or so of freeboard, the driver engaged the two propellers driven by off-takes from the rear sprockets (hence ‘duplex drive’) and headed for Sword Beach, the most easterly and most critical of the Normandy landing zones. If things went well, in 50 minutes’ time it and 39 others of the 13th/18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary’s Own) would ‘touch down’ and give covering fire for the infantry who were to assault directly from their landing craft a few minutes later.

But there were plenty of things that could go wrong. The swell could overwhelm them or landing craft could run into them; engines could fail; there were mines and obstacles at both the high- and low-water marks on the beach; and the Germans could bring accurate fire to bear if they spotted them. Burn and his fellow crewmen (including his elder brother, who was the codriver and hull machine-gunner) could only hope that their DD would be so low in the water as to be barely noticeable but not so low that the waves would lap over the canvas screen. In the end they just had to trust their training.

The idea of the DD was that of the Hungarianborn engineer Nicholas Straussler, who in 1940 devised a practical method of increasing a tank’s buoyancy by means of a waterproofed canvas screen that, when erected, encompassed the top half of the tank, creating an upper canvas hull. On beaching, the screen could be quickly collapsed to allow the tank its full mobility and firepower. Straussler demonstrated the buoyancy principle to the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, by placing a brick in a canvas bucket and floating it in a paddling pool. He explained that a wheeled vehicle’s displacement being usually greater than its weight, it floated naturally; however, heavily armoured vehicles, having a density much greater than water, needed the fabric superstructure to increase its displacement.

The first trials took place in June 1941 with the lightest of tanks – the Tetrarch, weighing 7.5 tonnes – at Brent Reservoir on the north-west outskirts of London. These were followed by successful sea trials at Portsmouth. Having thus proved the concept, a heavier Valentine tank was adapted, with propellers driven directly from the gearbox, and tested in May 1942. It performed well, although it subsequently sank during a trial in which it was subjected to machine-gun fire. The canvas screens were never going to be able to withstand bullets or shrapnel but with such a low profile in the water the risk was deemed acceptable. The following month some 450 DD Valentines were ordered.

However, when in early 1943 the first American Sherman tanks began to appear, it was soon clear that despite their extra weight – twice that of the Valentine, necessitating a much taller flotation screen of some eight feet – they were far more suitable for the planned seaborne assault. Because the Sherman’s 75mm barrel was considerably shorter than the Valentine’s, it could be launched with its gun forward rather than traversed rear, and therefore be instantly ready to fire on touch-down when the screen was collapsed. Nevertheless, crews would do their preliminary training with the Valentine before conversion training on the Sherman.

Although the time and place of the invasion was still far from decided, the Hussars began preparation in April 1943. Their crews were first told that they were ‘to be put ashore in an entirely novel manner’, and were then made to sign the Official Secrets Act. Only on arriving in Suffolk later that month and parading on the edge of Fritton Lake did they learn they were to be a ‘water assault regiment’ and what exactly that meant, and why.

One of their officers, Captain Jasper Selwyn, who had been awarded the Military Cross while serving with the commandos in the disastrous Dieppe raid in August 1942, had seen the Churchill tanks put ashore directly from their landing craft, and then quickly put out of action, leaving the infantry without support. Furthermore, 33 landing craft had been lost on the way in too. The lesson of Dieppe was that tanks had to be in action on the beach before the infantry landed, and they could not be put ashore directly from landing craft.

The Hussars quickly mastered ‘tank watermanship’ on the tranquil lake. Tank seamanship was another matter, not least the real risk of inundation and sinking. Each tank had an inflatable dinghy, and the crew had ‘Mae West’ life jackets, but how might they escape from a tank that sank? The crews went to Gosport in Hampshire for familiarisation with the Davis submarine escape apparatus. “There was a big water tank for escape training,” Burn recalled. “We were dressed in denim and we had to get inside the empty tank and climb about 20 feet down a ladder and into a Sherman tank at the bottom. Once inside we had to sit in our positions and then the water was poured in. We had to wait till it was up to our chins and then put on a nose clip and turn on the oxygen. At that point divers would glide down from the top of the tank, tap us on the shoulder and that was our cue to get out of the tank and to make our way to the surface. Some of the lads forgot to take their nose clips off and were going red in the face. That was quite an experience, because I couldn’t swim.”

Having mastered seamanship, tactical training followed throughout the winter of 1943-44 in the Moray Firth near Inverness, and in the spring off the south coast. By June the regiment felt confident, although when the commander-in-chief General (later Field Marshal) Sir Bernard Montgomery assured them that what the Army was about to do on D-Day was “a perfectly normal operation of war” it must have sounded more than a little hopeful. It was no less than the most complex military operation ever undertaken.

On the night of 5 June – D Minus 1 – the Hussars had a rough crossing from Portsmouth with the wind at Force 5. All five of Burn’s crew threw up at least once into a bucket hung on the back of the tank (the planners had thought of everything). “It wouldn’t have bothered me whether the thing had sunk or not, I was so seasick,” said Burn. But now at first light they were in the water, making for Sword Beach at a steady 100 yards per minute. Standing on the turret to steer the tank by tiller was its commander, Lieutenant Derek Spencer. On the engine deck behind him, unable to see over the screen, stood three other members of the five-man crew: Burn, his brother Peter, and the loader/radio operator. Only at the last minute would they clamber inside, as per the drill. The driver himself could see nothing at all. The prototype DD had a Perspex window but it was ditched because it served no purpose other than to unnerve him, especially when seeing fish.

Burn’s and the other 33 Shermans of the Hussars’ two DD squadrons (six tanks could not be launched for various technical reasons) were now ‘sailing’ in line ahead by troops of four. Seeing nothing but the sky, all Burn could hope for was that the Germans couldn’t see either, that the swell rose no higher and that no landing craft ran into them. The columns fanned out into line abreast 1,000 yards from shore; 500 yards out Burn and the others climbed inside to prepare for touch-down, leaving Spencer atop the turret to conn the tank. Another 200 yards on, as the tracks made contact with the beach, the Germans opened fire. Spencer guided the driver another 100 yards or so, managing to avoid the steel obstacles with their Teller anti-tank mines, until the water was shallow enough to break the pneumatic struts to drop the screen.

Burn was at last able to see his targets, and suddenly realised “there was nothing and no one in front of us but Germans”. Thanks to his and the others’ suppressive fire, however, the infantrymen of the East Yorkshire and the South Lancashire regiments were able to land five minutes later and reach the sea wall with remarkably fewer casualties than the infantry at Dieppe. After the War, the Hussars would jauntily add four bars of A Life on the Ocean Wave to the regimental march.

But now it was time for the tanks themselves to get off the beach. Because they’d landed on a rising tide, water had flooded many engines, including Burn’s. Spencer called for his troop sergeant to reverse his own tank to the front of theirs to cross-load the machine guns and ammunition, and take off the crew. Meanwhile, Burn traversed and elevated his 75mm and fired off all the HE (high explosive) ammunition inland before jumping across to the other tank. Much to his satisfaction, his brother managed to save not just his machine-gun belts but also his tins of cigarettes. That night they bivouacked in Hermanville-sur-Mer just a mile inland, having found a replacement tank and fought all afternoon. Burn “slept out by the side of our tanks but then we were stonked [shelled]. So I immediately went under the tank and ever after that I always slept inside it,” he recalled.

The Hussars had lost three tanks during the ‘swim’ but they had been the only one of the eight British, Canadian and US regiments to launch and touch down as planned on their respective beaches – Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah. Others had launched much closer, on account of the sea conditions, and some straight from the landing craft where enemy fire was slacker. Of the 30 US tanks launched off Omaha Beach only two made it to shore.

Burn, a tailor’s salesman from Harrogate in North Yorkshire, had volunteered in 1942 as soon as he was old enough, and left the Army in 1947 in the rank of sergeant. He died in December last year, aged 99, the Hussars’ last veteran of the Normandy landings. To the end he remained in awe of the organisation of D-Day: “Whoever worked it out, it was wonderfully, wonderfully done.”

Allan Mallinson commanded the 13th/18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary’s Own) from 1988 to 1991.