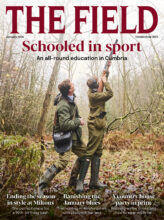

Man has been training birds of prey to hunt for the table for millennia. Sir Johnny Scott explains the fascinating history of an elegant pursuit that remains popular to this day

Falconry is one of the fastest-growing country pursuits, with 25,000 people (5,000 of whom hunt with hawks) involved, who between them keep about 75,000 birds of prey. There are more than 35 falconry centres and five national clubs (of which the British Falconers’ Club is the largest and oldest) plus a number of regional clubs. These offer opportunities to meet experienced falconers, learn about training and flying birds of prey, and attend field meets and social events. Falconry is currently inscribed by Unesco for 24 countries as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

(Read Sporting Dianas – Emma Ford, falconer)

Ancient falconry

The sport of falconry is immensely ancient – the first hunting birds of prey are believed to have been trained at around the same time in both the Mongolian steppes and in Persia 4,000 years ago. This knowledge gradually moved westwards; the Ancient Greeks trained and flew birds of prey, as did the Romans, Celts, Anglo-Saxons and Normans. The crusading knights met falconers in the Middle East who had taken the art to a level of sophistication far beyond that which existed in Britain, bringing back improved methods of husbandry and refined falconry techniques as well as exotic new breeds. For the monarch and nobility during the Middle Ages, falconry was a deadly serious pastime, considered among the finest of all earthly pursuits. However, it was much more than a mere amusement for the elite: hawking made an important contribution to the food chain. It was, after all, the only means of catching birds on the wing or holding them to the ground while a net was drawn over them.

A royal falconry hunt in India

Hawks required infinite patience, kindness, cleanliness and delicate treatment of damaged feathers, and a falconer was as highly regarded as a huntsman. He would have a pharmacopoeia of medicines and aworkshop of intricate tools for making and repairing the paraphernalia of falconry: the bells, swivels, varvels, jesses, leashes, gloves and the ornate plume-crowned hoods in the colours of the owners’ heraldic livery. Master falconers in royal or noble households were in great demand and able to command excellent salaries. The post was dignified by elevation to part of the royal households both here and in Europe, with the 1st Duke of St Albans being created Hereditary Grand Falconer of England. Today the King’s Grand Falconer is Murray de Vere Beauclerk, the 14th Duke of St Albans.

By the English Civil War in 1642, falconry had become the elegant diversion of a diminishing minority, and it went into a total decline during the troubled years of Cromwell’s Commonwealth. With the Restoration, as returning Cavaliers brought back lighter, more manoeuvrable continental shotguns, shooting became the fashion and the skilled mystery of falconry was kept alive by only a handful of ardent enthusiasts. There was a resurgence of interest in the mid-18th century, which has grown steadily ever since.

Falconry at The Game Fair

The most commonly used hawks in UK falconry are peregrine and gyr falcons. These tend to be flown over wide terrain where they use their magnificent stooping speed to take birds on the wing – grouse over pointing dogs, for example, which I would thoroughly recommend if you get the chance. Goshawks (the correct name for someone who flies a goshawk is an ‘austringer’) are superb hunters, ideally suited to all UK game species: pheasant, partridge, hare and wildfowl. The sparrowhawk, a smaller bird, is perfect for pigeon; redtailed hawks and Harris hawks, whose broad wings allow them to soar and drop on to their prey, are popular for rabbits and are terrific fun. Some years ago, I had a day bolting rabbits with my ferrets to a party of falconers with four Harris hawks, casting their birds to hang on the wind above the rabbit bank. It was fascinating watching them using their strength, velocity and persistence in pursuit of frantically jinking rabbits, stooping and rebounding with incredible aerial dexterity.

Hunting with a falcon on Dartmoor

Wild birds of prey have been protected in this country since the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 but falconers acquire stock from people who breed captive birds in the UK or by importing them under licence from abroad. The modern falconer needs a variety of different skills: sensitivity to his birds’ moods, well-being and ailments; knowledge of leatherworking; the ability to skin and butcher fresh food for the birds, and an understanding of game and other wildlife. Above all, they must have absolute commitment and dedication to creatures that are probably more temperamental and demanding than any other. The rewards, however, outweigh the long hours of training and devoted attention.