Extracts from A Twitch Upon the Thread, introduced and edited by Jon Day, including writing by Charles Dickens, Jonathan Swift, Charles Kingsley and more, from medieval times to the present day

In this edited extract from A Twitch Upon the Thead: Writers on Fishing, introduced and edited on Jon Day, writers from Charles Dickens to Virginia Woolf ponder the great pasttime of angling.

For more on a greatest angling writers, read best fishing books to hook and start adding to your ‘to read’ pile.

The Field is the ultimate sporting journal, and has been since 1853. SUBSCRIBE today with our best ever deal, SIX ISSUES for JUST £6, by clicking on THIS link.

A TWITCH UPON THE THREAD: WRITERS ON FISHING

VIRIGINA WOOLF: FISHING FROM THE MOMENT AND OTHER ESSAYS, 1947

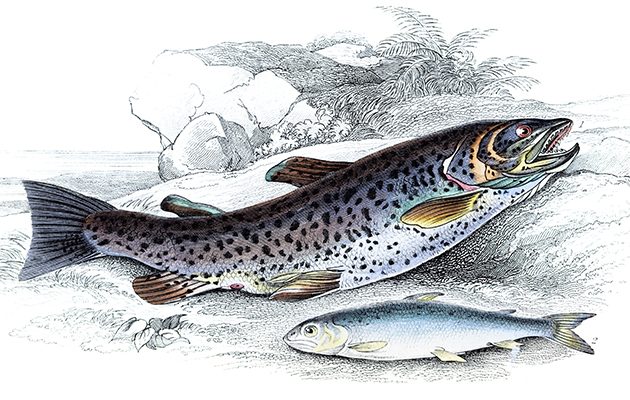

What does the fisherman dream? Of all the rivers rushing past – the Eden, the Test, and the Kennet, each river different from the other, each full of shadowy fish, and each fish different from the other; the trout subtle, the salmon ingenious; each with its nerves, with its brain, its mentality which we can dimly penetrate, movements we can mystically anticipate? Or does he dream of the wild Scottish hill in the blizzard; and the patch of windless weather behind the rick, when the pale grasses no longer bent but stood upright; or the vision on top – twenty Whooper swans floating on the loch fearlessly? Or does he dream of poachers with their whisky-stained weather-beaten faces? Or does he dream of places that his ghost will revisit if it ever comes to earth again – of Ramsbury, Highhead, and the Isle of Jura?

But here he wakes ‘with that sense of well-being which sleep in the open air always engenders. It was midnight, moonless and clear. I walked to the edge of the flat rock…’ The trout were feeding.

“What does the fisherman dream?”

CHARLES DICKENS: A DICTIONARY OF THE THAMES, 1893

Sturgeon occasionally come up the Thames, but they were never numerous in this river. Provision was made in ancient Acts excepting them from the vulgar fate of other fish, orders were issued that the sturgeon ‘was not to be secreted’, and that all royal fishes taken should be made known. The sturgeon therefore is always, when taken, sent direct to grace the table of majesty. They have never been known to be taken by line and bait, but they often get entangled in the nets of fishermen, which they greatly mutilate, from their amazing strength, in their efforts to escape.

The flesh of the sturgeon may be rendered into the choicest of dishes – one portion simulating the tenderest veal, another that of the sapid succulence of chicken, and a third establishing its reputation to a claim to most of the gastronomic virtues of the flesh of many acceptable fish in combination. The great chefs, Francatelli and Ude, used to aver that there were one hundred different ways of rendering sturgeon fit for an emperor; and Soyer would boast that he had added two more methods of its culinary preparation to these apparently exhaustive receipts.

JEROME K JEROME: THREE MEN IN A BOAT

The neighbourhood of Streatley and Goring is a great fishing centre. The river abounds in pike, roach, dace, gudgeon, and eels, just here; and you can sit and fish for them all day.

Some people do. They never catch them. I never knew anybody catch anything, up the Thames, except minnows and dead cats, but that has nothing to do, of course, with fishing! The local fisherman’s guide doesn’t say a word about catching anything. All it says is the place is ‘a good station for fishing’.

The Angler’s Guide to the Thames says that ‘jack and perch are also to be had about here’, but there the Angler’s Guide is wrong. Jack and perch may BE about there. Indeed, I know for a fact that they are. You can see them there in shoals, when you are out for a walk along the banks: they come and stand half out of the water with their mouths open for biscuits. And, if you go for a bathe, they crowd round, and get in your way, and irritate you. But they are not to be ‘had’ by a bit of worm on the end of a hook, nor anything like it – not they!

“I never knew anybody catch anything, up the Thames, except minnows and dead cats.”

I am not a good fisherman myself. I devoted a considerable amount of attention to the subject at one time; but the old hands told me that I should never be any real good at it, and advised me to give it up. They said that I was an extremely neat thrower, and that I seemed to have plenty of gumption for the thing, and quite enough constitutional laziness. But they were sure I should never make anything of a fisherman. I had not got sufficient imagination. They said that to gain any position as a Thames angler, would require more play of fancy, more power of invention than I appeared to possess.

Some people are under the impression that all that is required to make a good fisherman is the ability to tell lies easily and without blushing; but this is a mistake. Mere bald fabrication is useless. It is in the circumstantial detail, the embellishing touches of probability, the general air of scrupulous – almost of pedantic – veracity, that the experienced angler is seen.

JONATHAN SWIFT: A LETTER TO LORD BOLINGBROKE, THE WORKS OF JONATHAN SWIFT, 1841

I remember when I was a little boy, I felt a great fish at the end of my line which I drew up almost on the ground, but it dropt in, and the disappointment vexeth me to this very day.

CHARLES KINGSLEY: CHALK STREAM STUDIES, PROSE IDYLLS, NEW AND OLD, 1874

So we will wander up the streams, taking a fish here and a fish there. We have the whole day before us; the fly will not be up till five o’clock at least; and then the real fishing will begin. Why tire ourselves beforehand? The squire will send us luncheon in the afternoon, and after that expect us to fish as long as we can see. For is not the green drake on? And while he reigns, all hours, meals, decencies, and respectabilities must yield to his caprice. See, here he sits, or rather tens of thousands of him, one on each stalk of grass – green drake, yellow drake, brown drake, white drake, each with his gauzy wings folded over his back, waiting for some unknown change of temperature, or something else, in the afternoon, to wake him from his sleep, and send him fluttering over the stream; while overhead the black drake, who has changed his skin and reproduced his species, dances in the sunshine, empty, hard, and happy, like Festus Bailey’s Great Black Crow, who all his life sings “Ho, ho, ho,”

“For no one will eat him,” he well doth know.

However, as we have insides, we had better copy his brothers and sisters below, and settle with them upon the grass awhile beneath you goodly elm.

“Detachment of mind, and freedom and independence of spirit, are among the charms of angling.”

Comfort yourself with a glass of sherry and a biscuit, and give the keeper one, and likewise a cigar. He will value it at five times its worth because it raises him in the social scale. He holds “a good cigar is the mark of the quality”, and of them who “keep company with the quality”, as keepers do. He puts it in his hat-crown, to smoke this evening in presence of his compeers at the publichouse, retires modestly ten yards and instantly falls fast asleep. Poor fellow! he was up all last night in the covers, and will be again to-night. Let him sleep while he may, and we will chat over chalk-fishing.

SIR EDWARD GREY, VISCOUNT FALODEN: FLY FISHING, 1899

It is the plain indiscriminating desire for success which leads us to the second stage in angling, that of taking the pains and trouble necessary to acquire skill. In early years we are content to catch fish anyhow but we find that the greatest number can be hooked using artificial flies. It becomes our object to learn this art and to improve in it by practice. At first the young angler, wholly bent upon success, may value his skill chiefly for its results: he dwells upon these, compares each good day, is probably competitive and anxious that his basket should be as heavy as those of others. But as long as this lasts an angler has not yet attained to the greatest enjoyment of his sport. He is missing more pleasure than he gains; and he is preventing himself from having that detachment of mind, and freedom and independence of spirit, which are among the charms of angling.

LEONARD MASCALL: ‘THE CARPE’ A BOOK OF FISHING WITH HOOKE AND LINE, 1590

The Carpe is a straunge and daintie fish to take, his baites are not well knowne, for he hath not long béene in this realme. But now many places are replenished with Carpes, both in poundes and riuers. He is a straunge fish in the water, and very straunge to byte, but at certaine times to wit, at foure a clocke in the morning, and eight at night be his chiefe byting times, and he is so strong enarmed in the mouth, that no weake harnesse will hold him. The red worme and the Menow bee good baites for him in all times of the yeare, and in Iune with the cadys or water worme: in Iuly, and in August with the Maggot or gentyll, and with the coale worme, also with paste made with hony and wheate flower, but in Automne, with the redde worme is best, and also the Grashopper with his legs cut off, which he wil take in the morning, or the whites of hard egges stéeped in tarte ale, or the white snaile.

“Sometime that night, I finally forswore the gentle art of fishing.”

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON: ‘A LETTER OF JM BARRIE’, 13 JULY 1894, THE LETTERS OF ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, VOLUME 22

It was a charming stream, clear as crystal, without a trace of peat – a strange thing in Scotland – and alive with trout; the name was something like the Queen’s River. It formed an epoch in my life, being the end of all my trout-fishing. I had always been accustomed to pause and very laboriously to kill every fish as I took it. But in the Queen’s River I took so good a basket that I forgot these incites; and when I sat down to take my sandwiches and sherry, lo! and behold, there was a basketful of trouts still kicking in their agony. I had a very unpleasant conversation with my conscience. All that afternoon I persevered in fishing, brought home my basket in triumph, and sometime that night, ‘in the wee sma’ hours ayont the twal,’ I finally forswore the gentle art of fishing.

This is an edited extract from A Twitch Upon The Thread: Writers on Fishing, price £14.99, published by Notting Hill Editions.

The book is available to order online at: www.nottinghilleditions.com