The size of our terriers is no indication of bravery or personality, each one bred as the ideal opponent for its intended quarry, as Sir Johnny Scott explains

Size is nothing to go by when it comes to our smallest sporting companions. Terriers were bred carefully to be the ideal opponent to their quarry. Sir Johnny Scott takes a look at the history of terriers.

What they lack in size, they make up in spirit. Discover how terriers have become the top dogs of the country’s big houses, read terriers at the top: small dogs in stately homes.

THE HISTORY OF TERRIERS

At the Game Fair in 2019, I was wandering down Gunmakers’ Row when I found myself on a collision course with an elderly lady cradling a small, bright-eyed, smooth-haired, black-and-tan dog with a long, tapering muzzle and pricked lugs, not unlike a miniature Doberman Pinscher. In fact, as the good lady was quick to tell me, this was an English Toy terrier, known in America as the Toy Manchester, since it is regarded as a variety of the same breed as the standard size. Manchesters evolved in the early Industrial Revolution, when a whippet, or ‘snap dog’, was crossed with an old English Black & Tan terrier to create a dog that excelled both at ratting and coursing rabbits. Her cherished companion would be a direct descendant of a dog called Tiny the Wonder, who, in 1848 and 1849, at the height of rat-baiting popularity, held the record for killing 200 rats in under an hour. Tiny weighed only 5½lb and can be seen in action in the painting Rat-Catching at the ‘Blue Anchor’ Tavern, Bunhill Row, Finsbury, which hangs in the Museum of London. I felt this was probably not the moment to tell the owner she was cuddling a rat killer of such illustrious lineage, but it did make me wonder how many people have any idea what all the different breeds of terrier were actually bred for.

Manchester terrier Tiny the Wonder rat-catching at the Blue Anchor.

Until the late 1800s, terriers were loosely classified as four basic types: long-legged, wire-coated and probably black-and-tan dogs of the Welsh hill country and parts of Ireland; white dogs in the south and west country; rough-coated dogs north of Edinburgh, known collectively as Scotch terriers; whilst Northumberland, Cumberland and the Scottish borders had predominantly red or brown flat-coated terriers. There were, of course, an infinity of variations among these types to conform with personal preference or their intended use: badger, otter or fox. Each district would have a terrain and quarry species that governed the type of terrier bred there – short legs and hard to ground might suit in one area, where a longer-legged type would be more appropriate in another. Geographical isolation led to a preponderance of line breeding and the only opportunity for an outcross was meeting someone with a likely looking terrier at the little local markets or if a seasonal labourer or passing gypsy happened to have one.

Increased mobility during the Industrial Revolution, when roads improved and railways opened the country up, led to agricultural shows and great improvements in all livestock, as the best in one area were selected to improve those in another. Dog shows became phenomenally popular after the first, purely for setters and pointers, was organised by the gunmaker WR Pape and held at the annual Newcastle Cattle sale in 1859, with JH Walsh, editor of The Field, as one of the judges. Mixed breed class shows followed at Birmingham and London in 1860 and ’61; the Kennel Club was formed in 1873 and by the time Charles Cruft held his ‘First Great Show of all kinds of Terriers’ at the Royal Agricultural Hall, Islington, in 1886, with 57 classes and almost 600 entries, many of the old, amorphous regional working terrier types were becoming established as distinct breeds. They included the following.

JACK RUSSELL

None of the short-bodied, stumpy-legged little terriers, known as Jack Russells, full of mischief and joie de vivre, would have been recognised by the famous Devonshire sporting parson as having any resemblance to the dogs he bred. Russell described his foundation bitch, Trump, as, “white with a patch of dark tan over each eye and ear while a similar dot, not larger than a penny piece, marks the root of the tail. The coat, which is thick, close and a trifle wiry, is well-calculated to protect the body from wet and cold but has no affinity with the long rough jacket of the Scotch Terrier. The legs are straight as arrows, the feet perfect, the loins and whole frame are indicative of hardiness and endurance, while the size and height of the animal may be compared to that of a full-grown vixen fox.”

Russell wanted terriers that could run with hounds, were bold enough to bolt a fox or lie with it whilst it was dug out. Essentially, he wanted terriers that were sensible enough not to get hurt and he prided himself on being able to say that none of his ever had. The Parson terrier, finally recognised by the Kennel Club in 1990, is probably nearer to the original, or the Fox terrier – Russell was a founding member of the Kennel Club and helped write the breed standard for the Fox terrier. He never showed his own breed and on the day of his funeral in 1883, all Russell’s breeding notes and records were last seen blowing about the yard of his house at Swimbridge. It is highly unlikely any terriers today can claim to be a descendant of Russell’s, but there are any number in hunt kennels of whom Russell would have said, “Now they are the right sort.”

SKYE & CAIRN

Skye terriers, a painting from 1881.

Until the 19th century, when selective breeding for type and colour became fashionable, the highly regarded Scotch terriers were described as being of two sorts: one, a very strong type with a long coat, short legs and elongated back, bred principally for bolting otter and badger, which became known as the Skye terrier; the other sort were, “rough coated and beautifully formed, having a shortened body and more sprightly appearance”. Among these is the Cairn, known as the Short-haired Skye terrier until the breed was renamed in 1909, bred for bolting foxes from among the cairns where highland foxes tend to hole up and for general vermin control, which included everything from a rat to a wildcat. They were quite bold enough to take on an otter; in the 1890s, Captain Macdonald of Waternish in north-west Skye kept a pack of 40 Cairns that he used regularly for bolting otters from cairns formed by fallen rocks along the sea shore below the cliffs at Waternish Point.

DANDIE DINMONT

With their low-set, long, flexible body, shaggy coat and stumpy legs, Dandie Dinmonts are one of the historic terrier breeds of the Scottish Borders. Bred by the sporting farmers, shepherds and gypsies for bolting badger and otter, they were said to fear nothing with a hairy skin. Now a very rare breed, the Dandie Dinmont of today is believed to descend from dogs owned by a gypsy known as ‘Piper Allan’ in the latter decades of the 18th century; his terriers were renowned across Northumberland.

John Ferneley Jnr’s portrait of a Dandie Dinmont, a historic breed of the Scottish Borders.

Lord Ravensworth offered him 50 guineas for one after Allan cleared otters from the lake at Elsingham Park, and the Earl of Northumberland is said to have offered him a rent-free farm for another, both of which he refused. The breed is named after the character in Sir Walter Scott’s novel Guy Mannering (1815), based on the sporting farmer James Davison of Hyndlee in Roxburghshire, who had several terriers of Allan’s breeding. Descriptions of them in Scott’s novel led to their immediate popularity, with the Dandie Dinmont Terrier Club being formed in 1875 and the breed standard created by William Wardlaw Reid.

BORDER TERRIER

1929 Border champion Ben of Tweeden.

Border terriers are probably the most popular pet among the terrier breeds, with their broad skull, short muzzle, slightly protuberant eyes and flat, wiry coat. A close relative to the Dandie Dinmont, they were referred to as the Coquetdale or Redesdale terrier from the area of the Cheviot hills where they were most commonly found. Bred for bolting foxes, they were quite courageous enough to take on badger and otter, but canny with it and knew when to keep out of trouble. From the late 18OOs they became known as Border terriers from their long association with the hunt of the same name. The Robson and Dodd families, who had owned and hunted the hounds for several generations, were famous for breeding hardy, working terriers, long enough in the leg to follow hounds. Borders were recognised by the Kennel Club in 1920 and are one of the few breeds to have remained true to type.

BEDLINGTONS

The curly-coated Bedlington.

These curly-coated, leggy terriers with their high, rounded skulls and long, tapering muzzles, share a common ancestry with both the Border and Dandie Dinmont, with a whippet cross somewhere in their genealogy. They were the archetypal general-purpose vermin and rabbiting dog, much favoured by the ‘Border muggers’, as the gypsies based at Yetholm were known, as well as Border farmers. James Davison of Hyndlee was among those who kept a pack of terriers made up of what were to become known as: Dandie Dinmonts, for otter and badger; Border terriers, for fox; and Bedlingtons, that had the reputation for fighting anything their own weight to the death and for running down whatever bolted. Originally known as Rothbury terriers, Bedlingtons became popular for racing and rabbiting with the miners of the Northumbrian coalfields in the early 19th century, hence the name.

SEALYHAM

A Sealyham, pictured in the 1930s.

This terrier was bred from 1850 until his death in 1891 by Captain John Tucker-Edwardes of Sealyham House in Pembrokeshire, principally for bolting otter and badger. Tucker-Edwardes was dissatisfied with his existing ‘mongrel’ terriers and set about breeding his ideal: a small, strong, brave, active terrier with short legs, a harsh white weatherproof coat and a strong jaw. He kept no records of the mix but it is believed he used Welsh Corgi for length of back, White West Highland from his friend Colonel Malcolm for colour and the now-extinct Cheshire terrier, a small type of Bull terrier, for breadth of jaw and courage. Tucker-Edwardes’ terriers became well known and highly regarded for their pluck and intelligence; they were officially recorded by the Kennel Club as Sealyhams in 1911. By 1935, the show dogs were described in Hutchinson’s Popular & Illustrated Dog Encyclopaedia as: “much too large and much too clumsy for the work they were originally bred for, and they would not have the ghost of a chance of getting even their heads into an otter’s holt”. Mercifully, enough of the working gene survived for Harry Parsons to form the Working Sealyham Terrier Club in 2008. Parsons has worked tirelessly to maintain this endangered breed and regularly hunts rats with a pack of 17 or so.

NORWICH

These immensely sporting little dogs and their close cousins, the drop-lugged Norfolk terrier, are the smallest working terrier breed but what they lack in size they make up by being extremely active, vocal, self-opinioned and bobbery. Reputably bred from local East Anglian ‘mongrel’ terriers and small, red, Irish terriers belonging to itinerant seasonal labourers, with possibly Cairn blood, they are great ratters and were often kept for controlling vermin in barns and stables. Known at one time as Cantab terriers, from their popularity with the university students, or Trumpington terriers, after the livery stables in Trumpington Street, where James Barrons the ostler bred a particularly sporting type. Both prick- and drop-lugged Norwich terriers were accepted by the Kennel Club in 1932, and in 1964 the drop-lugged type were reclassified as Norfolk terriers.

AIREDALE

The largest of the terrier breeds, Airedales, with their tight, weatherproof coats, were bred by crossing the old Black & Tan terrier of the north of England with an otterhound, to create a general-purpose dog that, although too big to go to ground, would be needle sharp and determined at anything above. Once known as the Bingley terrier, this cross proved to be incredibly clever and adaptable, with a good nose for following scent, capable of being broken to a gun and able to retrieve, both from land and water. Their unique characteristics were quickly recognised by Lt-Col EH Richardson, a specialist in dog handling and training, who provided Airedales for the Russian Army in 1904 to act as message carriers and to locate the wounded during the Russo-Japanese war. From 1908, he supplied Airedales to the North Eastern Railway police for patrolling dock areas. Airedales were extensively used during World War I by the military and Red Cross, and the many stories of their bravery and stoicism under fire brought them to public attention. They became very popular in the 1920s and ’30s but are now rather rare.

PATTERDALE

A particularly hardy type of terrier, known collectively as fell terriers, had been bred in Cumbria for centuries to run with the fell foot packs of the Lake District, where foxes have always been the scourge of the Lakeland sheep farmers. A fell terrier needed to be long enough in the leg to run all day with hounds, narrow in the chest to follow a fox when he went to ground in the rocky borrans, and tough enough to ensure that if he didn’t bolt, he wasn’t left alive. In 1873, the Matterdale and Patterdale hunts amalgamated to form the Ullswater and, in 1879, Joe Bowman became huntsman, a position he held pretty well continually for the next 45 years. Bowman bred old-fashioned working Border terriers, but used an outcross to a local fell terrier, now known as the Lakeland, to breed a terrier type he named the Lakeland Patterdale, after the valley he was born in. Patterdales became famous after Brian Nuttall began breeding them in the 1960s from Bowman’s line, which had been bred true to type by Cyril Breay and Frank Buck before World War II.

SCOTTISH

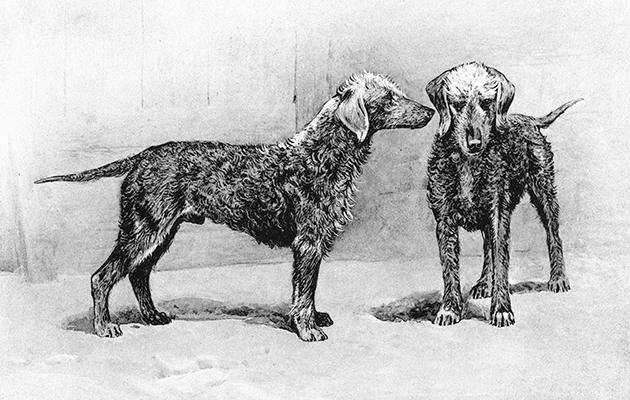

Two Scottish terriers, painted by Arthur Wardle.

Originally known as the Aberdeenshire terrier and bred for bolting fox, badger and otter, among other Highlands vermin, these immensely hardy, determined terriers were more like a Skye terrier, with their powerful jaw, low-slung bodies and short, sturdy legs, than their close relatives the Cairns or White West Highland. Captain Gordon Murray was responsible for standardising the breed in 1879 and Scotties were to become immensely popular after James Buchanan, the whisky magnate, marketed a brand of whisky with a label depicting a White West Highland and a Scottie. Famous owners of Scotties include Queen Victoria, Presidents Roosevelt, Eisenhower and Bush, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Rudyard Kipling, GK Chesterton and Hitler’s girlfriend, Eva Braun.

WHITE WEST HIGHLAND

The West Highland White breed was standardised by the 16th Laird of Poltalloch.

Light-coloured or off-white Scotch terriers had been around for centuries before King James I sent six from Argyllshire to France, as a gift for Henry III. Several of Edward Landseer’s paintings of the early 19th century portray light-coloured Scotch terriers, especially Dignity and Impudence, depicting the head of a pure white terrier sharing a kennel with a bloodhound, which perfectly captures the pricked lugs and keen, alert expression of these little dogs. A close cousin of the Cairn and sharing all their pluck and intelligence, we have Colonel Edward Malcolm, 16th Laird of Poltalloch, to thank for standardising the breed. Legend has it that Malcolm was so horrified at accidentally shooting one of his brown terriers, which he mistook for a hare at his estate near Lochgilphead, that he determined never to make the same mistake again by breeding pure white ones.