Numbers are possibly at an all-time low but, as Mike Swan explains, the best hope for some of our enchanting, endangered waders is on moors managed for grouse

Endangered waders are suffering long-term decline, and little of it well documented. Mike Swan suggests a solution that may allow us to continue to enjoy the magical song of the curlew. We need to look to the habitat of another bird, the grouse.

It seems that the topic of conservation will be forever surrounded by dispute and conflict. Rob Yorke explains why we must end the conflict and work together in conservation conflict: ending the conflict.

ENDANGERED WADERS

There can be little more magical than hearing the bubbling song of the curlew rolling across up-land pastures on a sunny morning in spring. I may be a bit of a heathen, but for me the song is even more evocative because I count curlew among my greatest wildfowling successes. Long ago, before they were protected by The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, curlew were both a difficult quarry and a substantial meal for me as an unemployed student with limited income. Once, on a wild and gale-torn dusk, I pulled off two right-and-lefts at flighting curlew, and fed royally for several evenings on the resulting casserole – those were the days.

The golden plover has a good density in the north of mainland Scotland, in particular over the Flow Country.

Taking the curlew, and several other endangered waders including redshank and grey plover, off the quarry list was in part a response to their populations already being in decline, but did it do any good? Well, as far as I can see, there is no evidence that it did anything even to slow the reduction in breeding numbers. In a way, this is hardly surprising; preventing exploitation will have an impact only if that exploitation is having a damaging effect, and we knew even back then that the usual evil of habitat loss was at least partly to blame for these declines.

ENDANGERED WADERS: WADERS OF THE MOORS

Different wader species have different habitat requirements, different diets, and different migration patterns. Some species also have varying strategies between individuals; so some redshank, for example, are pretty sedentary, perhaps just flipping over the sea wall from their summer nesting sites to winter feeding areas on the shore. Others will move to inland nesting sites, including upland areas, and yet other birds go on long migrations to breed in the Arctic.

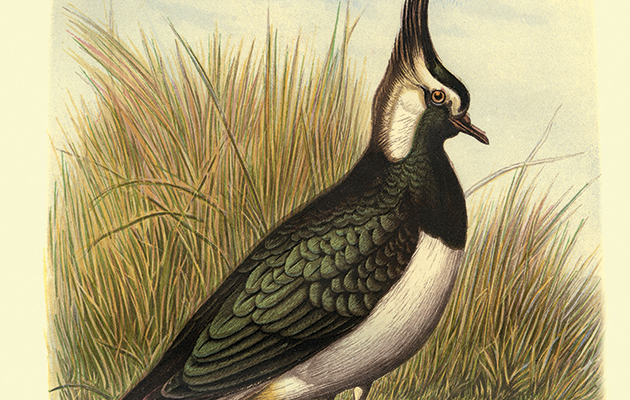

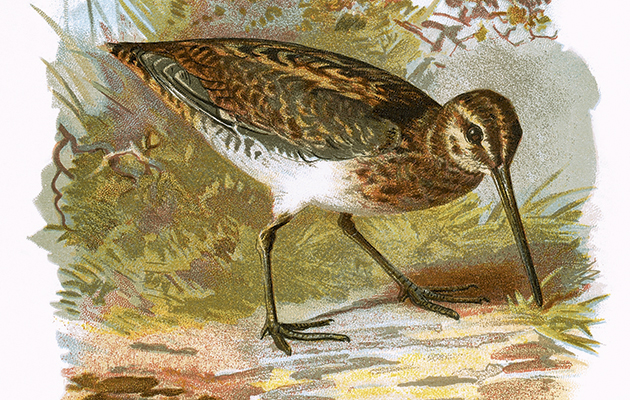

So, what wader species do we have breeding on the UK’s moors? Well there are several alongside the curlew. These include lapwing, golden plover, snipe, redshank and dunlin. Other species nest with us, too, such as the delightful dotterel, which inhabits our highest mountains, and the common sandpiper, which breeds alongside lochs, lakes and rivers, but neither really qualifies as a moorland bird. Indeed, even some of the “characteristic” moorland waders such as lapwing and curlew also choose other habitats – lowland heath, wet pastures and even arable farmland – while the dunlin comes down to sea level on the machair of the Western Isles.

Why moorlands should be so popular with this assemblage of birds is impossible to say, but all are ground nesters and all select open habitats away from woods. Many nest on the tundra of the far north; our moors are a similar habitat. The wetter parts of the moors offer suitable feeding habitat and an abundance of invertebrates suitable for foraging chicks.

ENDANGERED WADERS: HOW ARE OUR MOORLAND-BREEDING WADERS DOING?

Most of the endagered waders that breed with us are believed to have suffered long-term decline, little of it well documented. The first comprehensive breeding bird surveys of the UK were carried out for the British Trust for Ornithology’s breeding birds atlas in the late Sixties and early Seventies. There have been two further atlas surveys, the most recent in 2007-11.

Whatever the longer-term picture, it is fair to say that all the species in the “moorland as-semblage” have shown declines over the past 40 years but the picture is far from uniform. Curlew, for example, have suffered a large- scale reduction, especially in the west, with a 78% range contraction in Ireland and serious loss from the southwest of both England and Wales. They seem to have disappeared from the small colonies on the Surrey heaths where, as a boy, I used to marvel at their displays.

Lapwings have shown a similar dramatic reduction in their Irish range, although in this case it is just 50%. They have also shown serious range contractions in southwest England, west Wales and western Scotland. The good news is that they remain our most numerous nesting wader, and at least part of that is because they have pretty catholic tastes in habitat, nesting on a wide range of lowland habitats including arable farmland and damp pasture as well as upland sites.

Dunlin are much more wedded to the uplands in their choice of nesting sites, and their decline seems a little less dramatic, although there are serious losses where they do come down to sea level on the machair of the Western Isles. Here they will nest almost colonially in the rich limestone dune habitat, but introduced hedgehogs and, perhaps, American mink, have had a pretty dramatic effect through nest predation.

Golden plover seem to have fared rather better, and while there have been serious range reductions these have mostly been in areas where the breeding density was rather low anyway; the worst of these perhaps being in Ireland. The UK’s breeding snipe have declined somewhat, too, but most of this revolves around the lowlands, where agricultural intensification has probably been most dramatic. Worryingly, however, on some lowland reserves where habitat has been improved there has been little sign of recovery.

ENDANGERED WADERS ON GROUSE MOORS: THE GWCT’S UPLAND PREDATION EXPERIMENT

It is now generally accepted that average breeding densities of endangered waders are higher on moors managed for grouse, compared to ordinary moorland, and this was clarified in a scientific research paper published in the Journal of Applied Ecology in 2001. What was not so clear at this stage was the relative importance of habitat management and the grousekeepers’ predation control. To try to unravel this, the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust launched its Upland Predation Experiment on the moors around Otterburn in Northumberland between autumn 2000 and 2008.

The experiment was carried out over four separate but similar moorland beats, employing two full-time gamekeepers to carry out the legal predator control that any hill keeper would expect to do. One site was keepered throughout the experiment and one left to its own devices. Meanwhile, the other two sites were keepered for half of the experiment, with the keeper switching from one to the other midway. The sites had had little game management before the experiment began, and they had rather low wader densities by local standards. They had similar levels of heather burning and grazing throughout the experiment.

Four species of breeding endangered waders were monitored: curlew, lapwing, golden plover and snipe, and these were surveyed throughout, with both the numbers of breeding pairs and their success in fledging young recorded, although in practice snipe proved so secretive that it was impossible to measure nesting success. For the other three species, however, the average result was that they were three-and-a- half times as likely to fledge at least one young on a site with predation control as one without.

Now, this was clearly a great result, but it helps in the long term only if some of the extra young survive to breed and contribute to growth in the breeding population. Against this, it is also important to remember that, unlike the red grouse, these waders leave the moors in winter, in some cases for wintering grounds far away. Analysis of breeding den-sities showed that all three species returned to breed at higher levels in years following pre-dation control, and perhaps the most spectacular result was from lapwings, which showed an average 66% improvement each season.

ENDANGERED WADERS: BIODIVERSITY CONSEQUENCES

There are many in the world of conservation who will still be unconvinced that predation control matters. Some will argue that high densities do not matter, and that simply maintaining the so-called “upland bird assemblage” is the key thing for maintaining biodiversity. Perhaps without gamekeepers there would be fewer waders in the uplands, but the diversity of species would not be reduced? The trouble is there is no evidence to support this. At Otterburn the densities of curlew and golden plover were quite low compared with nearby grouse moors, but in years without predator control numbers continued to decline and there was nothing to suggest that they could persevere in maintaining their low density perpetually.

ENDANGERED WADERS: WHERE ARE THE WADERS?

As we have seen from the species accounts, the moors of the south-west of England and the hills of Ireland and Wales have not fared well for most species. Similar declines have occurred in the Lake District and many western parts of mainland Scotland. Here both range contractions and population declines are often at their most dramatic.

In most cases this is despite the fact that these areas have had considerable spending through agri-environment schemes to im-prove habitat for conservation. It would appear that these schemes are doing better at halting landscape change than at maintaining or improving biodiversity. Another common denominator is that there are rather few upland gamekeepers in most of these places.

If you read the species accounts in the latest BTO atlas a common theme begins to emerge: some of the highest densities occur in the Outer Hebrides, Orkney, and Shetland. These islands are fox-free places, where one might assume that predation pressure is naturally that bit lower than over the mainland as a whole.

Some birds, such as golden plover and dunlin, have good densities in the north of mainland Scotland and, in particular, over the Flow Country. While foxes may not be absent here, they are probably at a pretty low density. One of the earliest radio tracking studies was carried out near Erribol and suggested a density around a tenth of lowland England’s. The bird atlas shows low crow density here, too.

Where else might you expect to find high breeding wader densities at the regional scale? Well, the Pennine region of northern England stands out. Here perhaps the highest national density of grouse moors and upland keepering coincides with Special Protection Areas set up specifically for endangered waders. Indeed, if you break the area down to its individual Sites of Special Scientific Interest, you will even find that higher local wader densities tend to occur on the ones with the highest percentage of the ground being managed as grouse moor.

ENDANGERED WADERS: A BETTER FUTURE?

I started with the song of the curlew but that is just a part of the story; just as a wood should ring with birdsong on a spring morning, so the hills should ring with the song of myriad waders, bubbling curlew, piping golden plover, gambolling peewits and the background buzz of drumming snipe, to name but a few. Clearly, if you want this to happen, you must have the habitat right, for no species will thrive without somewhere suitable to live. However, it is essential to realise that these moors are a man-made environment, not a pristine wilderness. If left to their own devices these wonderful places will not self-maintain. They are what they are because of the history of human management, and that includes controlling the predators that impinge on human activity. Keeping them going as grouse moors keeps them alive and vibrant.